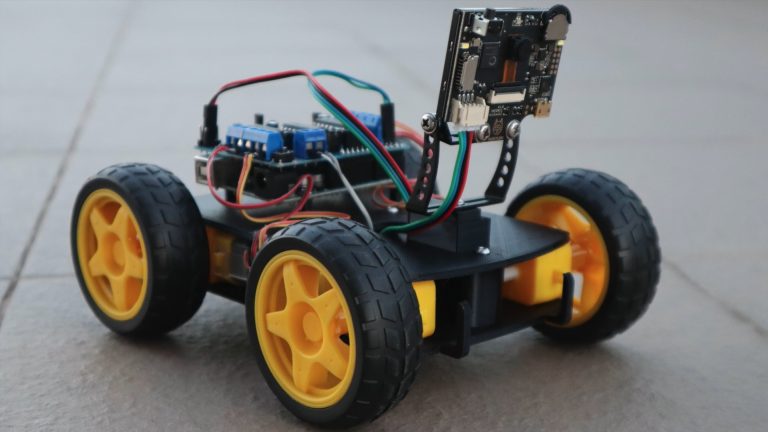

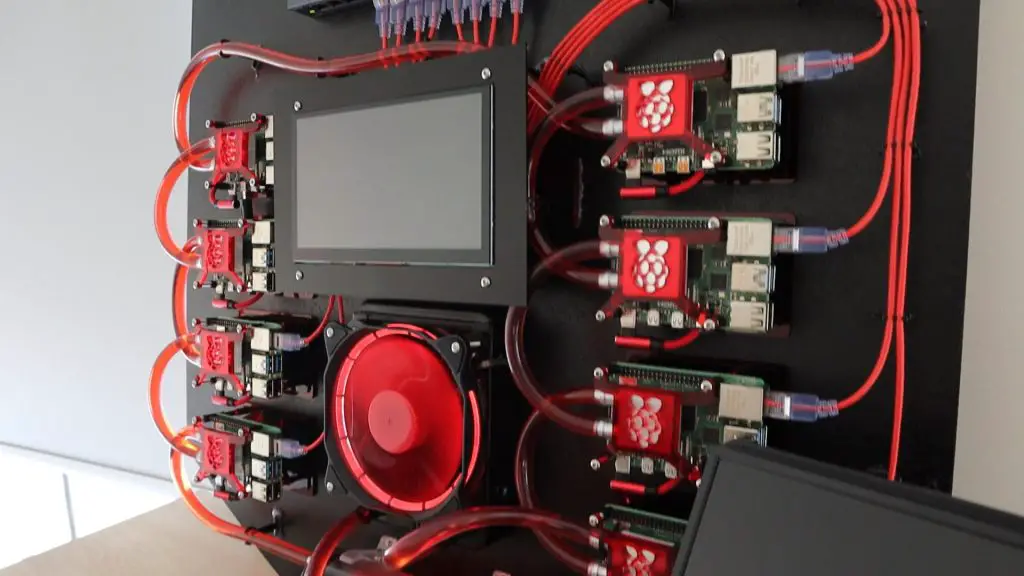

Today I’m going to be looking at adding AI line and object tracking to my previously built obstacle avoiding robot using a Huskylens.

A Huskylens is a standalone sensor with a couple of preconfigured recognition algorithms that allow you to easily add AI powered machine vision to your Raspberry Pi and Arduino projects.

It’s got built in object tracking, face recognition, object recognition, line tracking, colour detection and tag recognition and the best part is that it doesn’t require any internet connection to run. All of the processing is done locally on the Huskylens.

Here’s a video of the modifications done to the robot car as well as the car following lines and tracking objects, read on for the write-up and code:

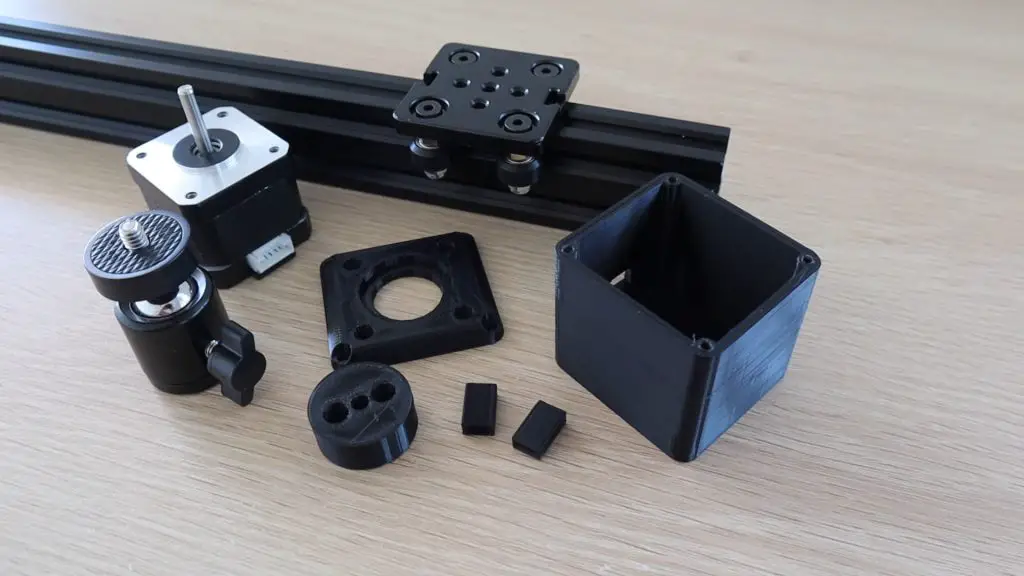

What You Need To Build Your Own AI Powered Robot Car

- Arduino Uno – Buy Here

- L293D Motor Driver Shield– Buy Here

- Huskylens – Buy Here

- 4 x Geared DC Motors & Wheels – Buy Here

- 9-12V Battery Pack

- 8 x M3 x 15mm Socket Head Screws – Buy Here

- Ribbon Cable – Buy Here

- Header Pins – Buy Here

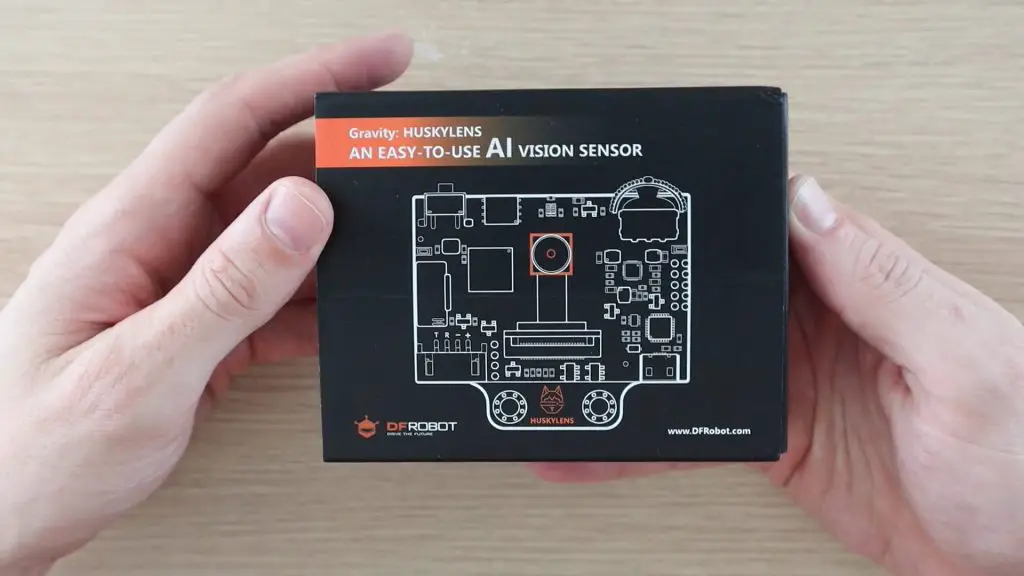

Unpacking The Huskylens

This Huskylens was sent to me by DF Robot to try out and share with you.

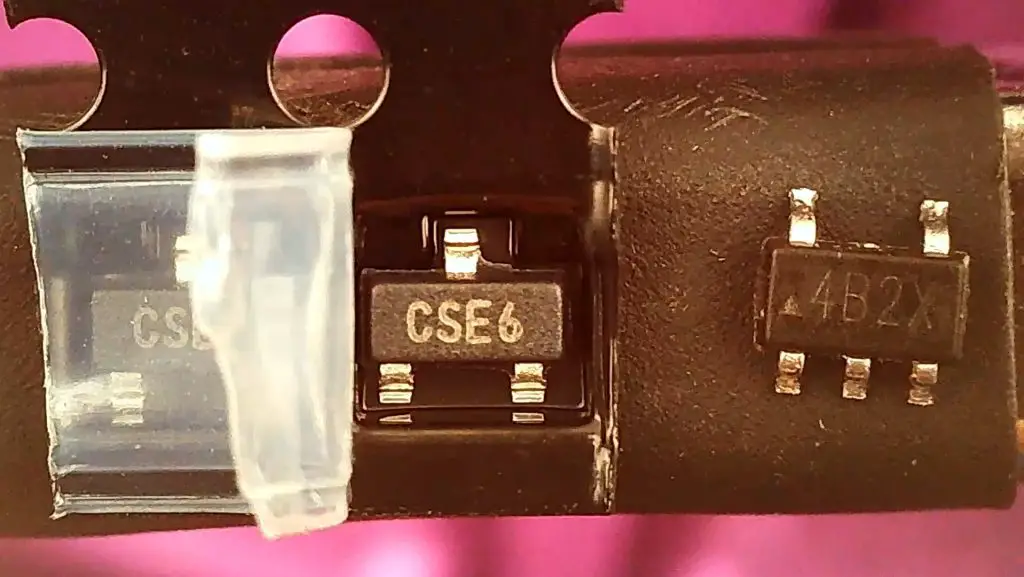

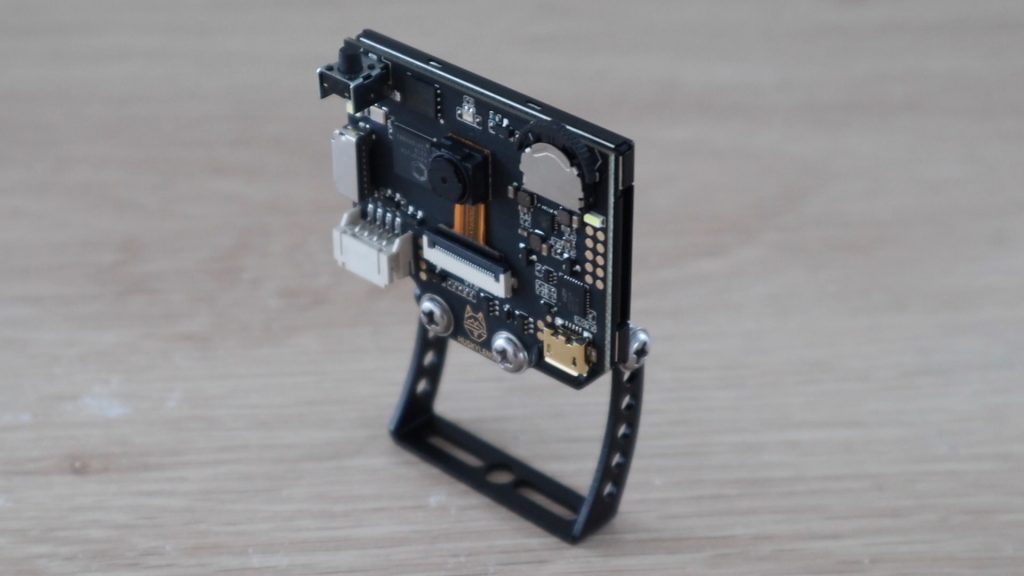

The Huskylens comes well packaged in a black bubble wrap sleeve within a two compartment box. Measuring just 52mm x 44.5mm, it’s smaller than an Arduino Uno or Raspberry Pi, it’s about the same size as a Micro:bit.

The device has two primary inputs. A multifunction menu selector and then a learn button, which allows you to select and learn new objects, faces and tags directly on the built-in 2-inch display. So you don’t need a PC with you to change modes or select different tracking objects.

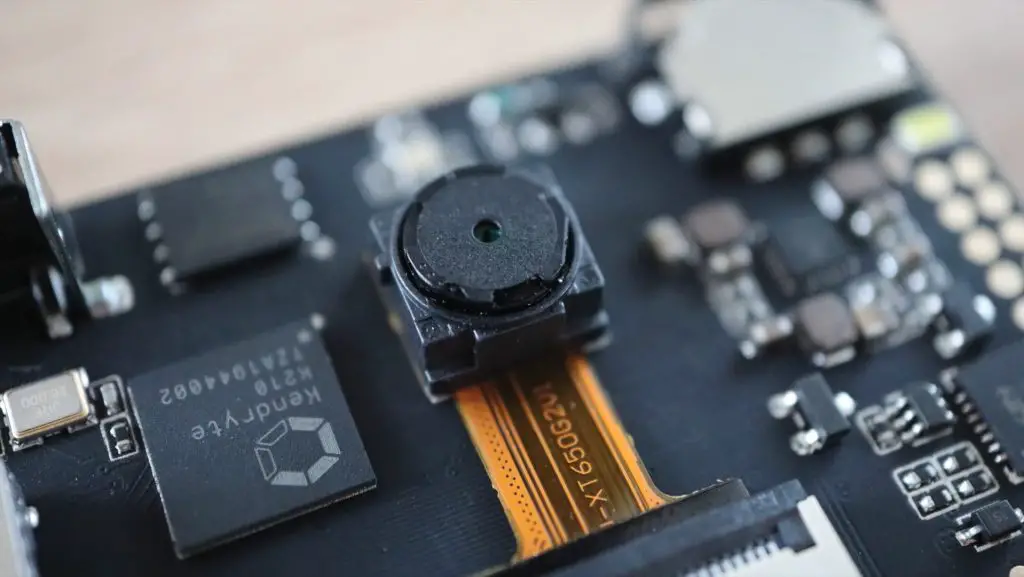

An OV2640 2.0 Megapixel Camera on the front is the Husklen’s “eye”.

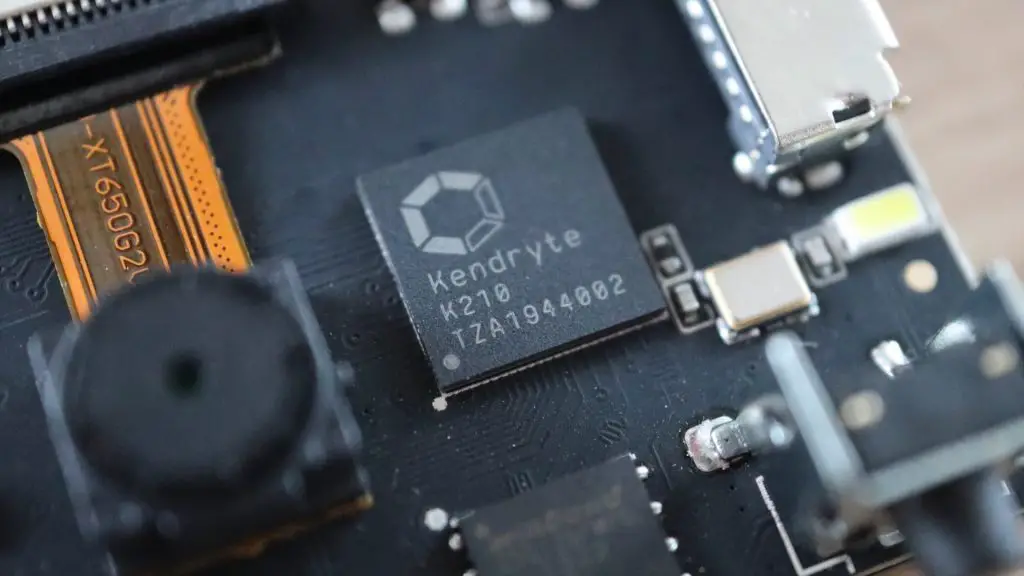

It uses a Kendryte K210 AI chip to run a neural network, which results in pretty impressively fast learning and recognition. Even with relatively fast-moving objects.

In the second compartment in the box you’ve got a mounting bracket, some screws and the cable to connect it to a microcontroller.

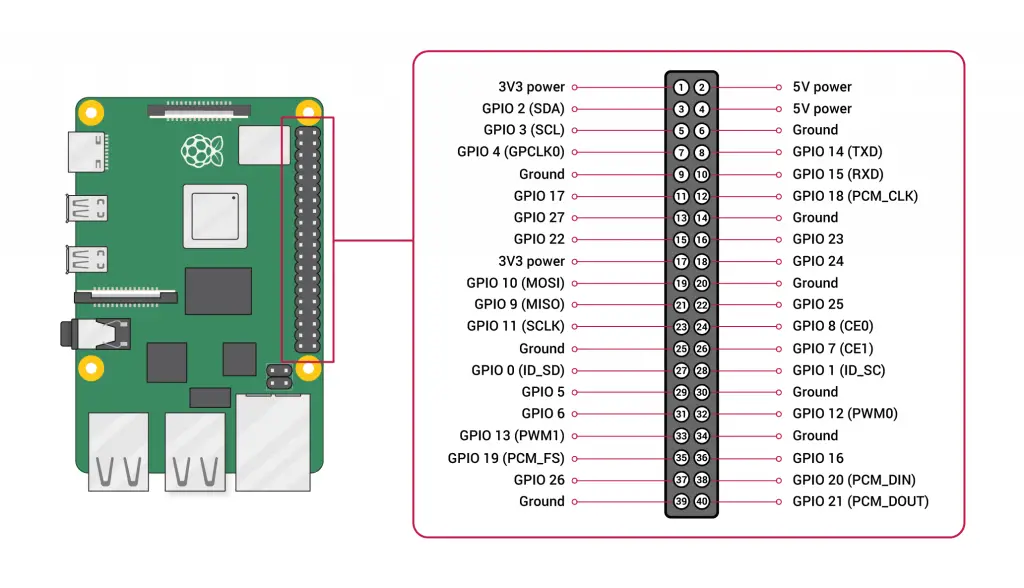

One thing that’s worth noting is that the included cable has female Dupont/jumper connectors on it. This makes it directly usable with a Raspberry Pi, which has male GPIO pins, but you’ll need to make up an adaptor to use it with an Arduino Uno or LattePanda which typically have female pins.

The Huskylens runs on 3.3-5V and consumes around 320mA at 3.3V or 230mA at 5V, so its perfect for battery powered projects as well.

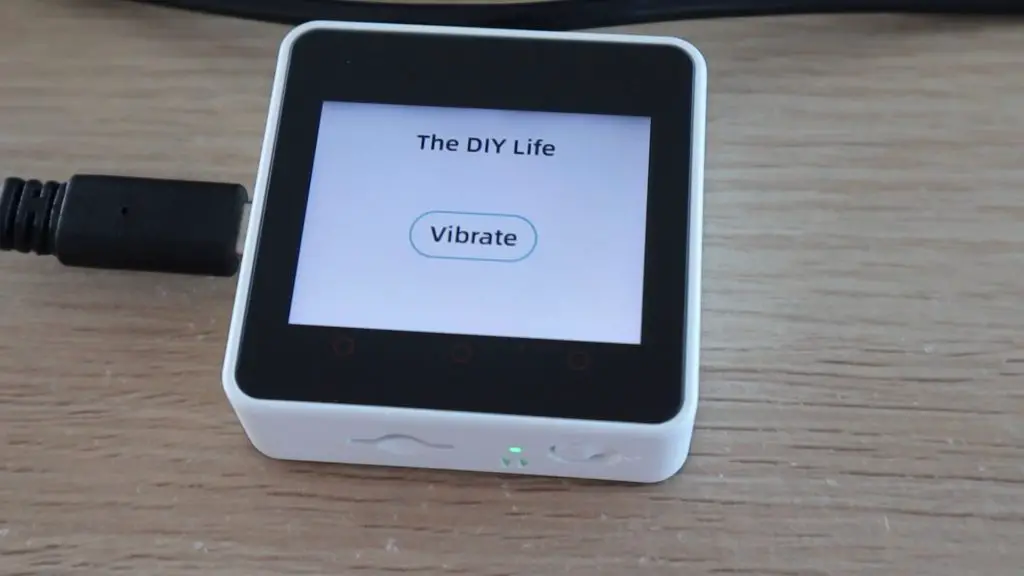

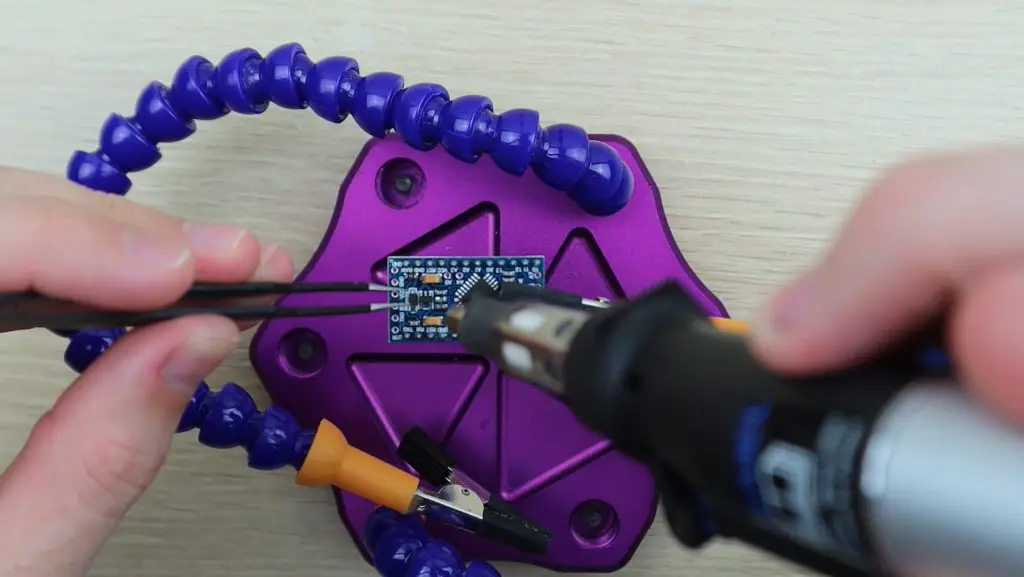

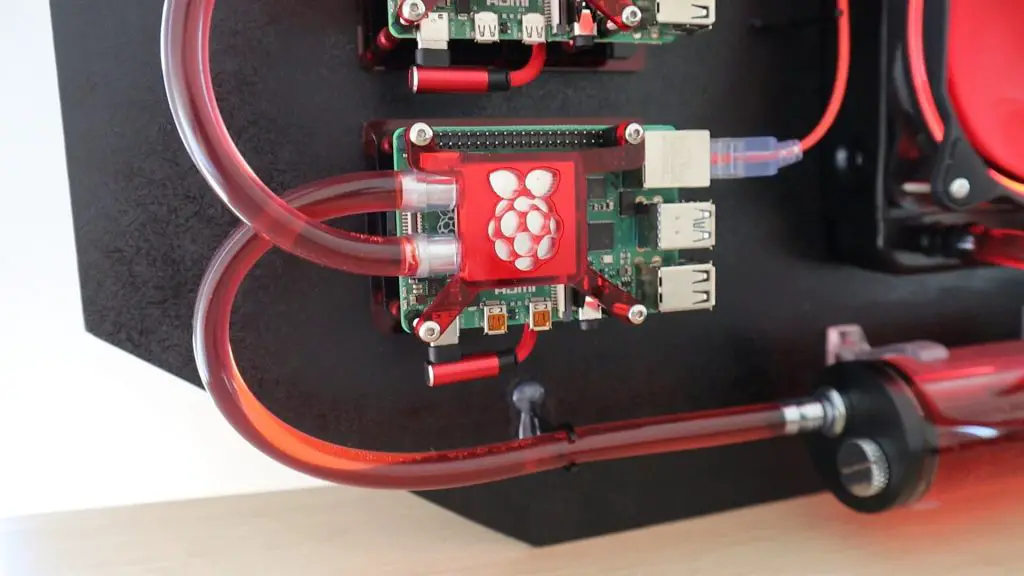

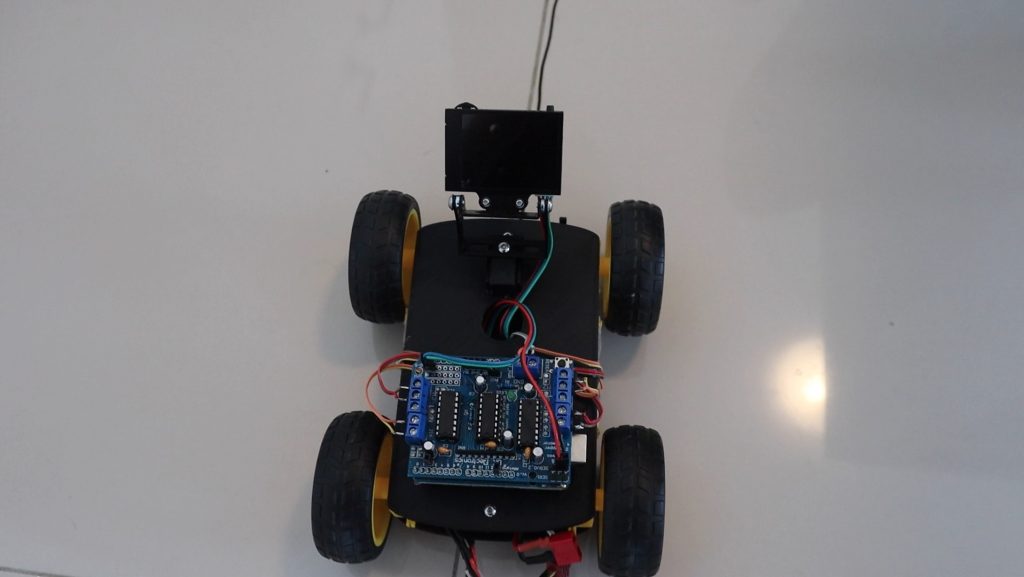

Adding The Huskylens To The Robot Car

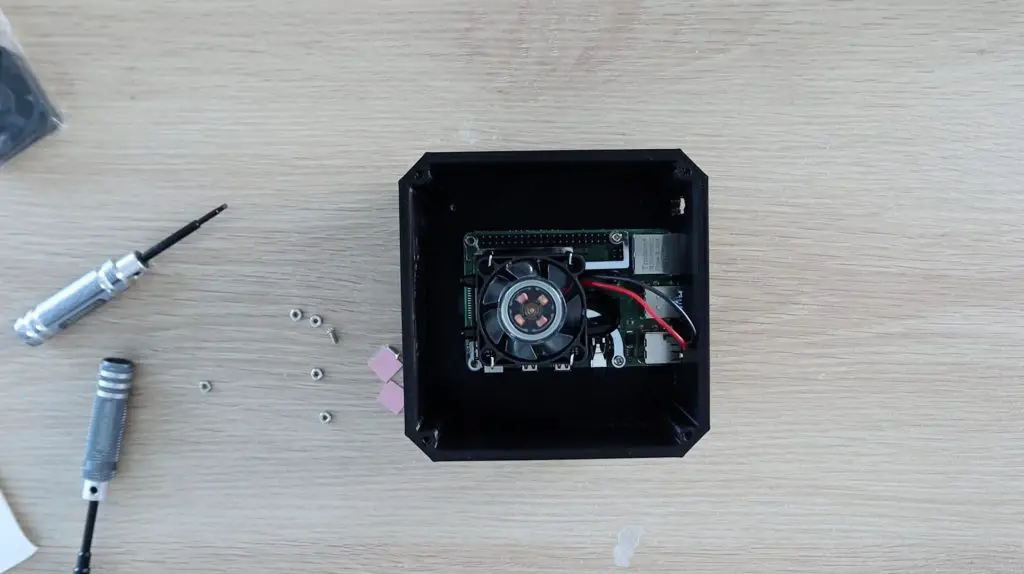

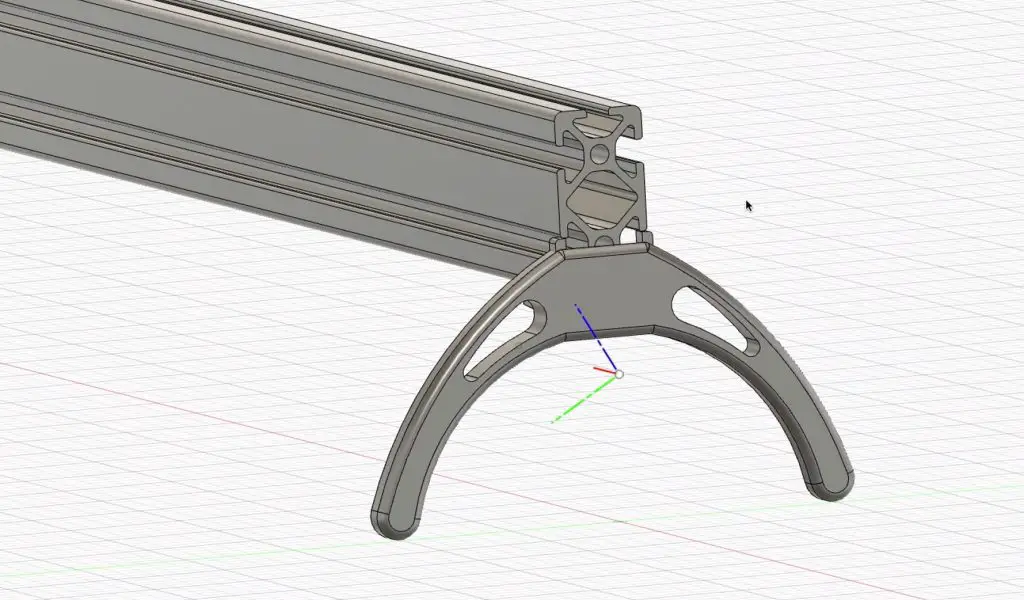

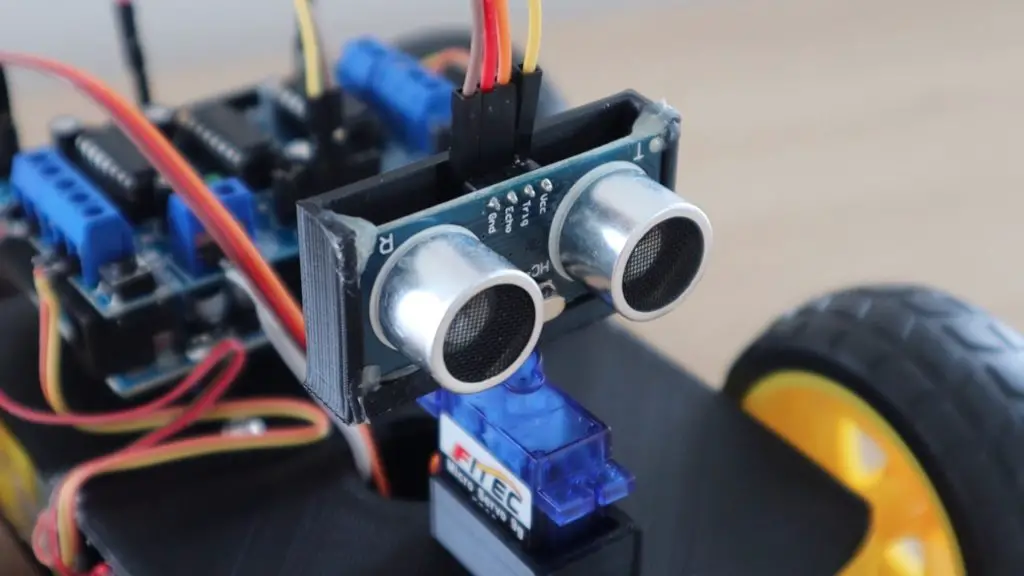

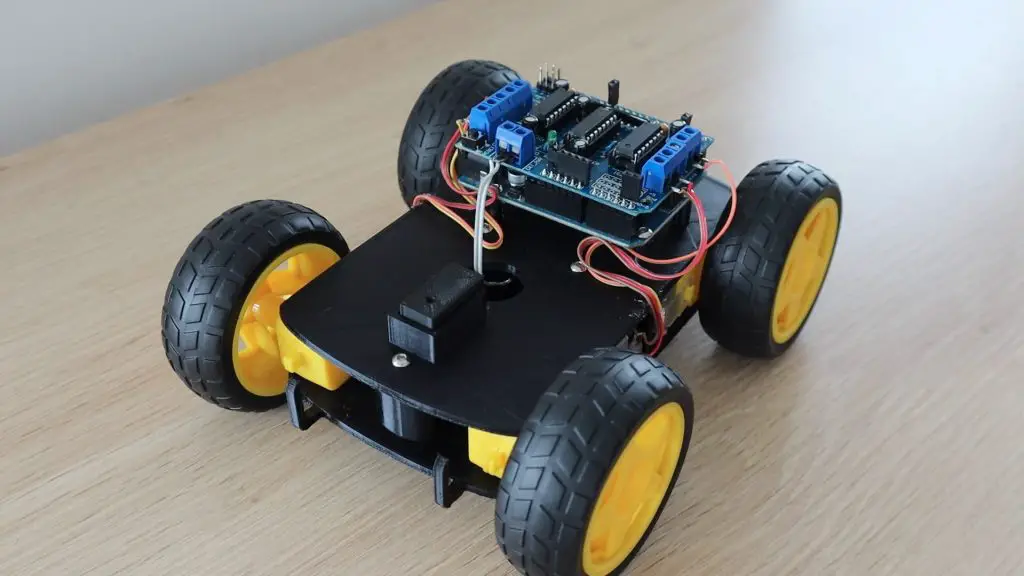

I’m going to be installing the Huskylens in place of the servo and ultrasonic sensor on the robot car which I built previously. Visit the previous build guide for the 3D print files for the car as well as assembly instructions, obviously leaving out the servo and ultrasonic sensor.

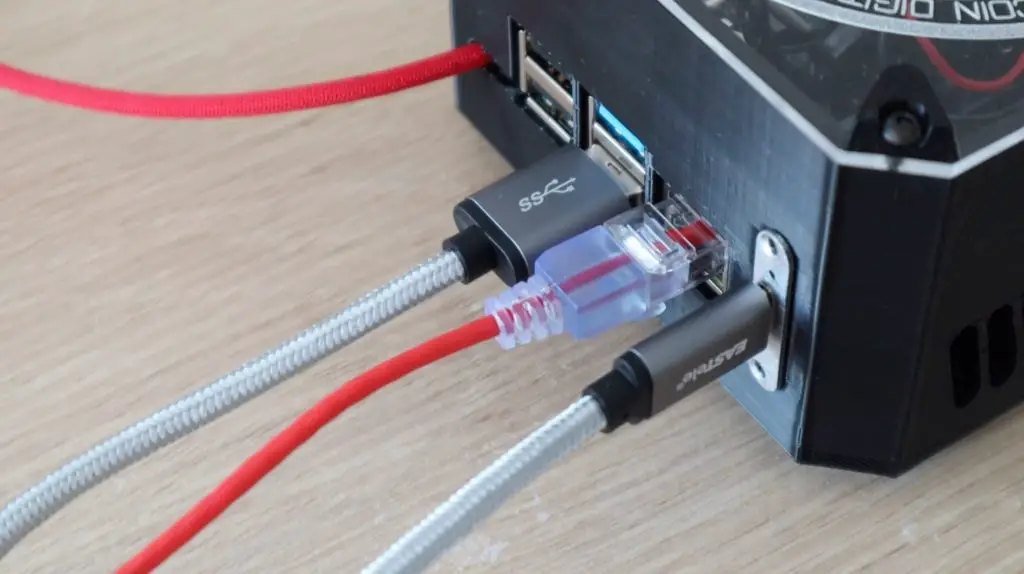

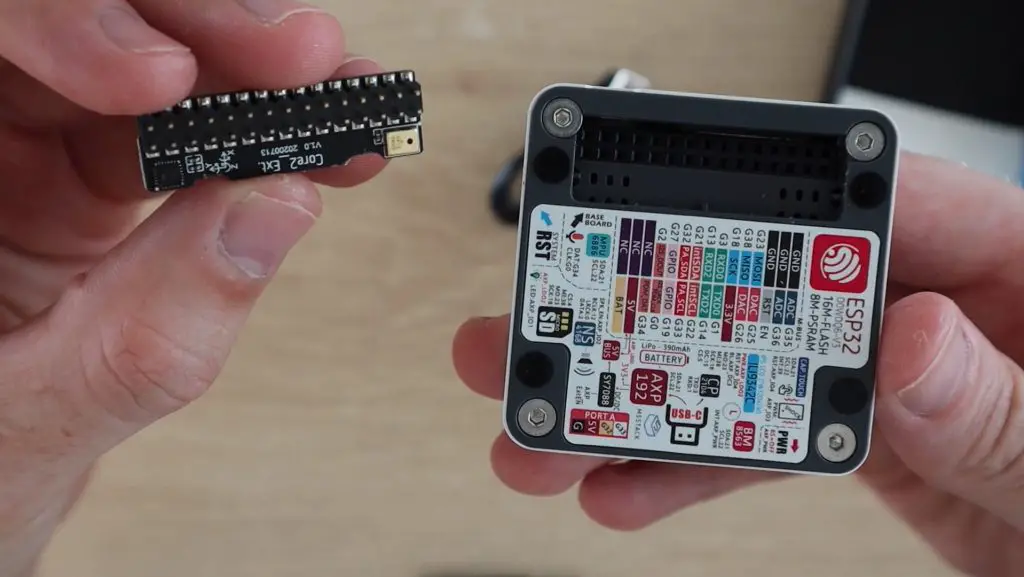

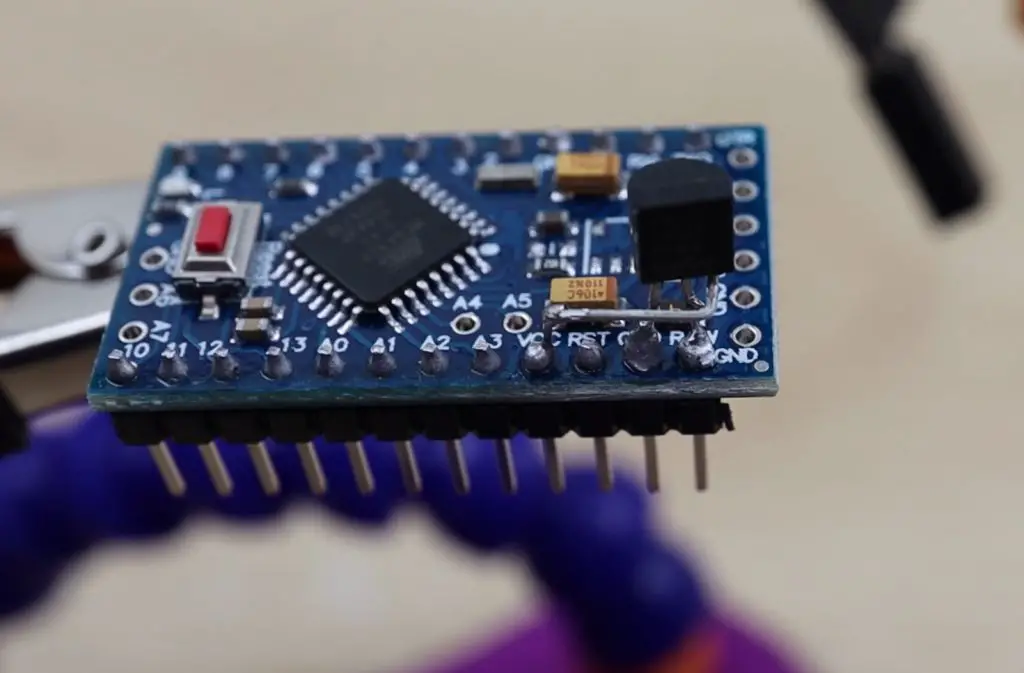

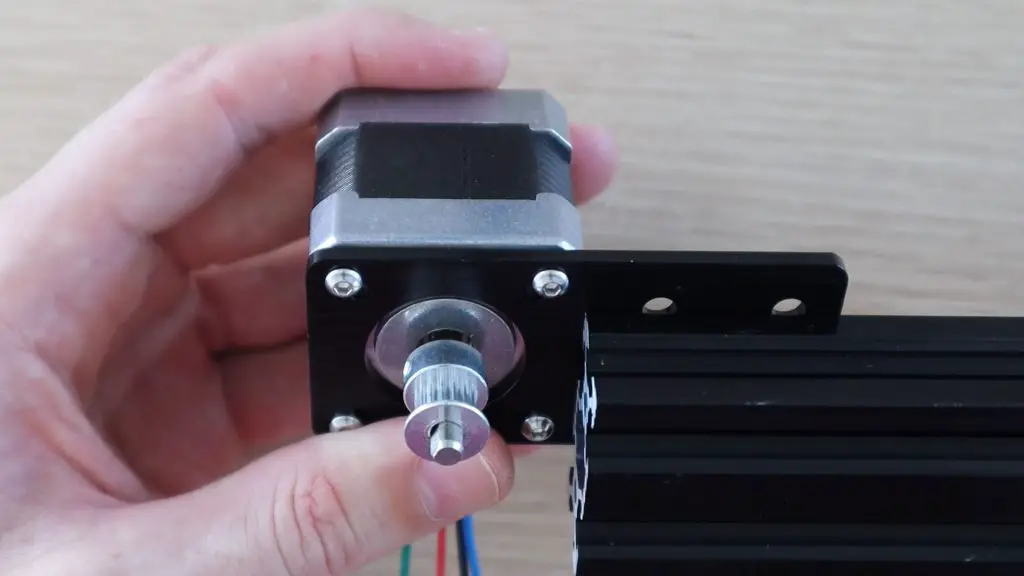

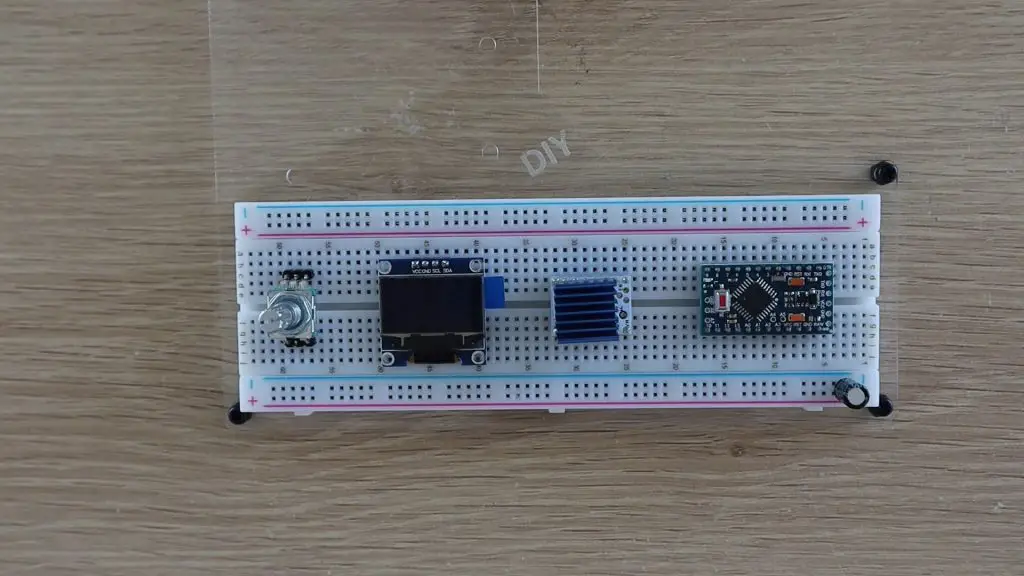

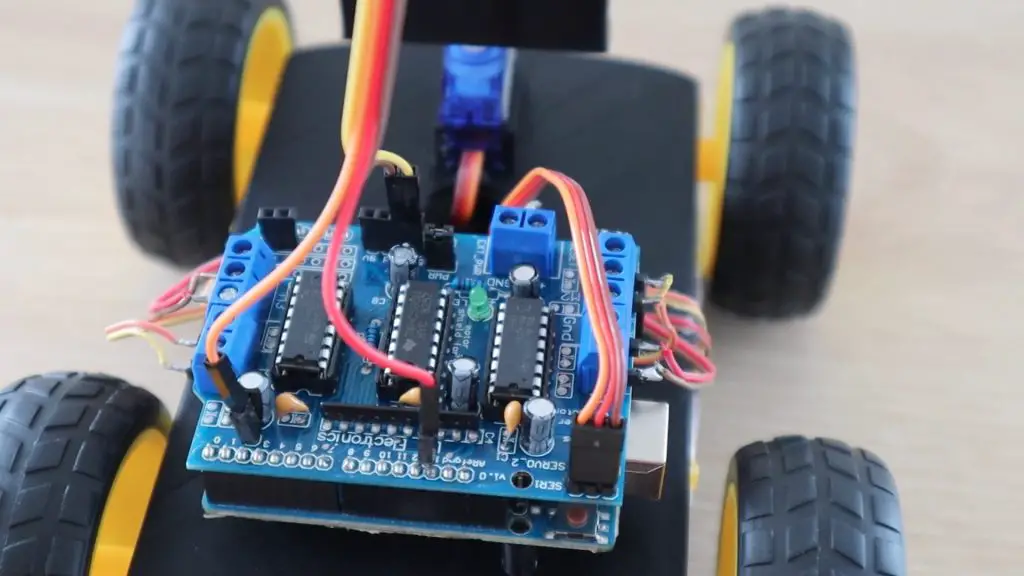

The car uses an Arduino Uno and a dual L293d motor driver shield to drive four wheels through some geared motors.

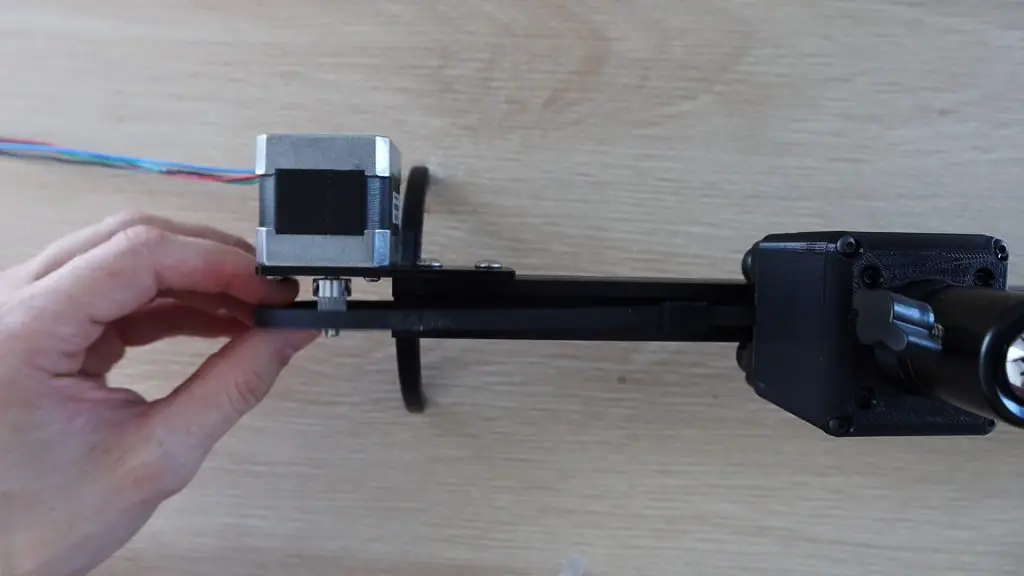

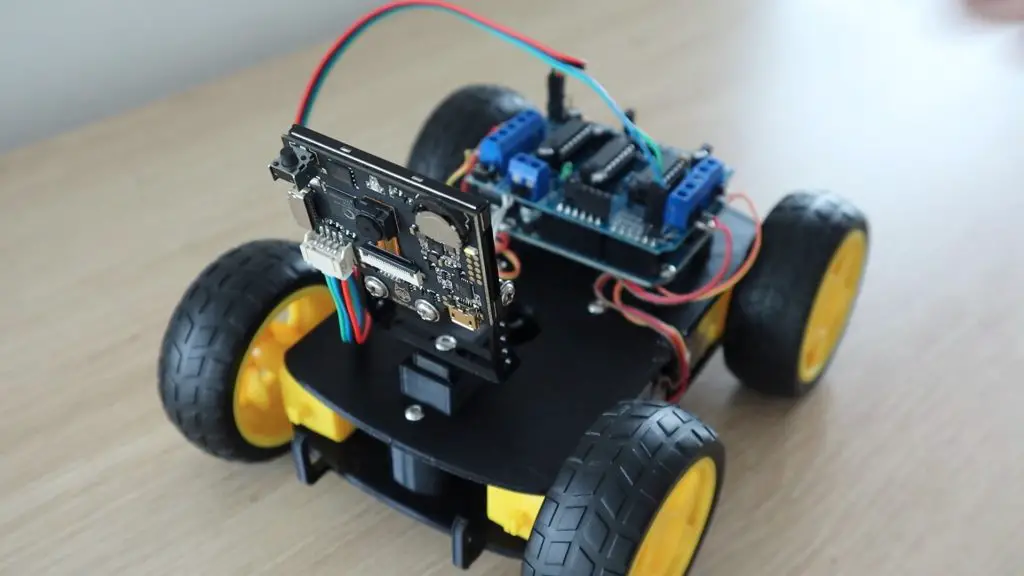

I’ll be mounting the Huskylens onto the bracket which is supplied with it. The bracket is somewhat universal in that it’s got a mounting pattern which could be fixed with a single screw, two screws or mounted onto a servo arm.

I’ve 3D printed a small adaptor block to fit into the servo holder on the robot car to screw the bracket into. I just glued this bracket into place using a glue gun.

I secured the bracket using a single M3x8mm screw through the centre hole.

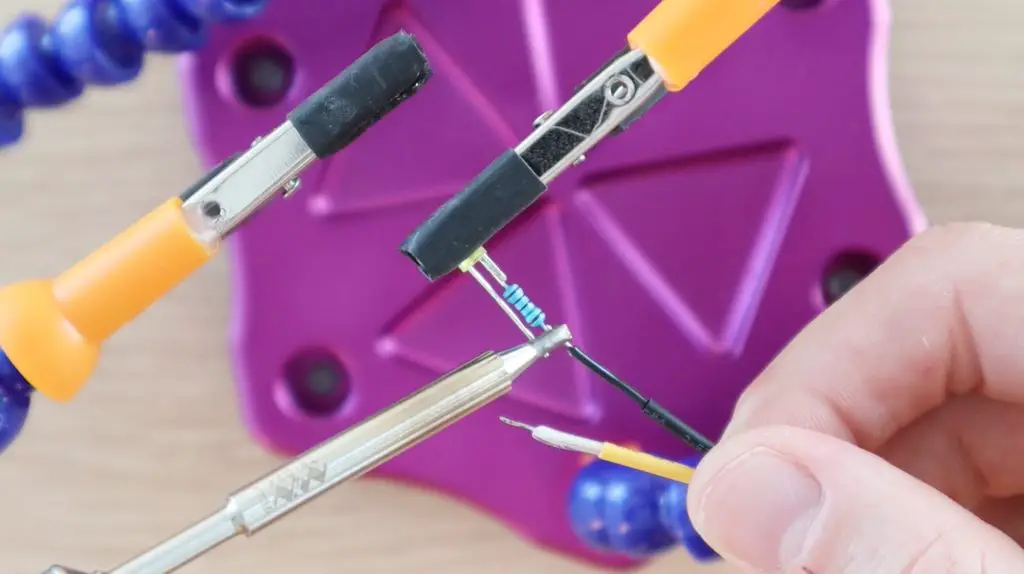

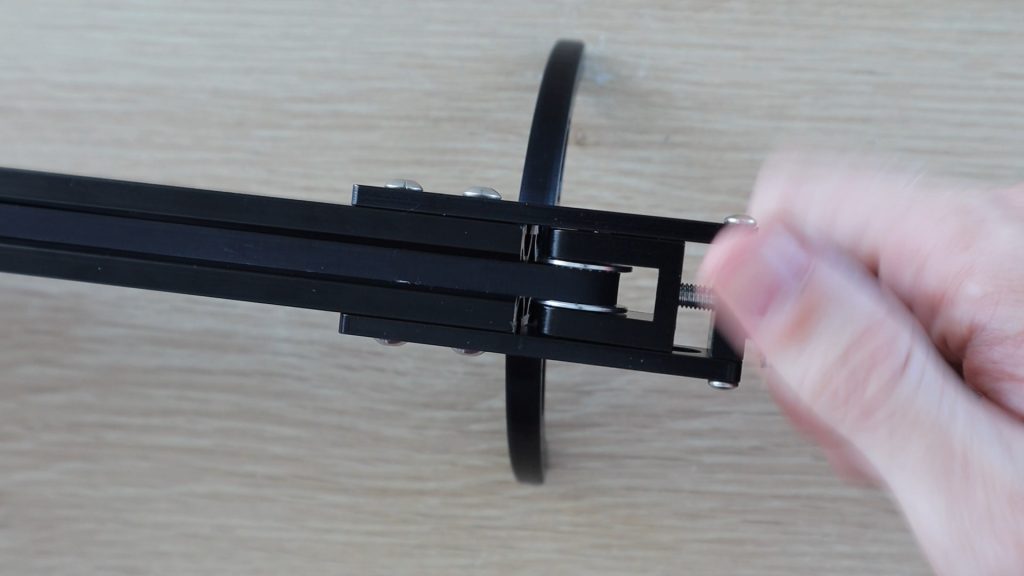

The Huskylens can communicate using I2C or SPI communication, I’m going to be using I2C because these pins are still available on the motor driver shield. Just like any other I2C device, there are four connections to be made, two for power and two for communication.

I used the GND and 5V pins from one of the servo outputs and then connected the SDA and SCL wires to A4 and A5 respectively.

Now that it’s installed, let’s power it up and have a look at the line and object tracking functions.

Experimenting With Line Tracking

We’ll start by powering up the Huskylens and switching it to line tracking mode.

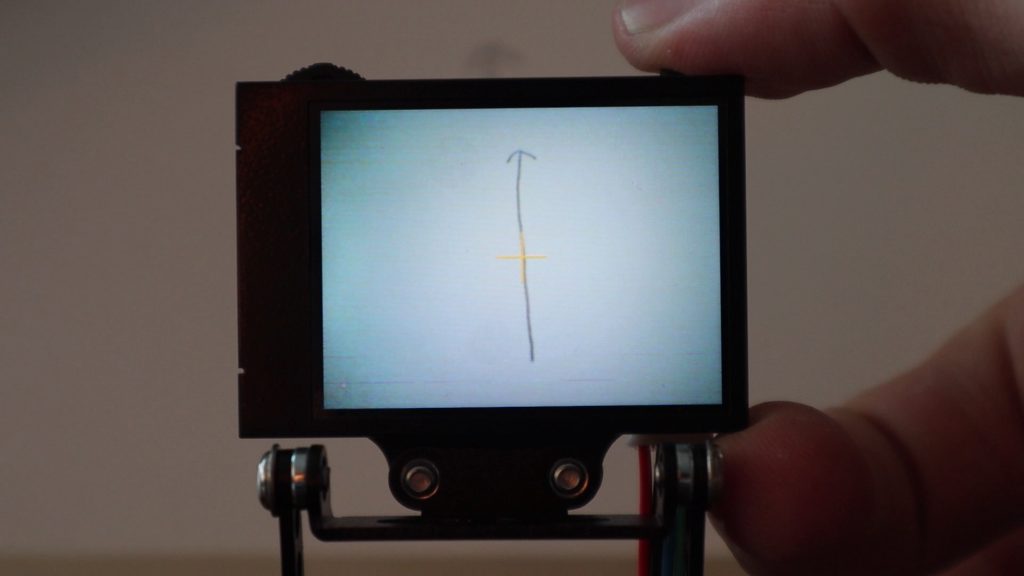

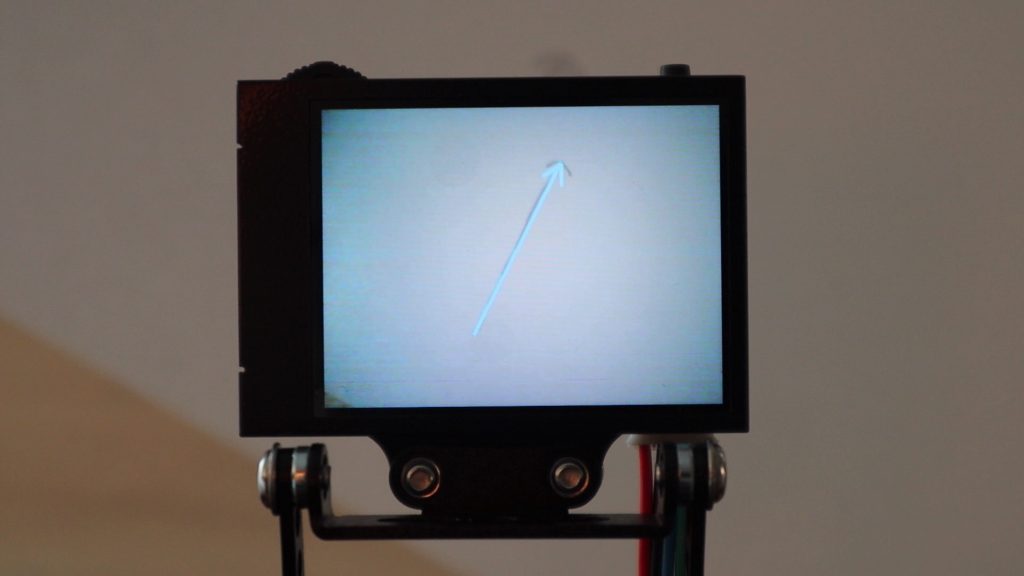

I’ve drawn a black arrow on a piece of paper, so let’s see how well it is able to pick it up.

We first need to point the crosshair in the centre at the line and then press the learn button to tell the Huskylens that this is the type of line it needs to follow.

You’ll then see it recognise the line and overlay a blue arrow which follows the line around on the display.

The Huskylens is actually impressively fast when tracking a line and picking up direction changes, even when the line is removed and then brought back into the field of view.

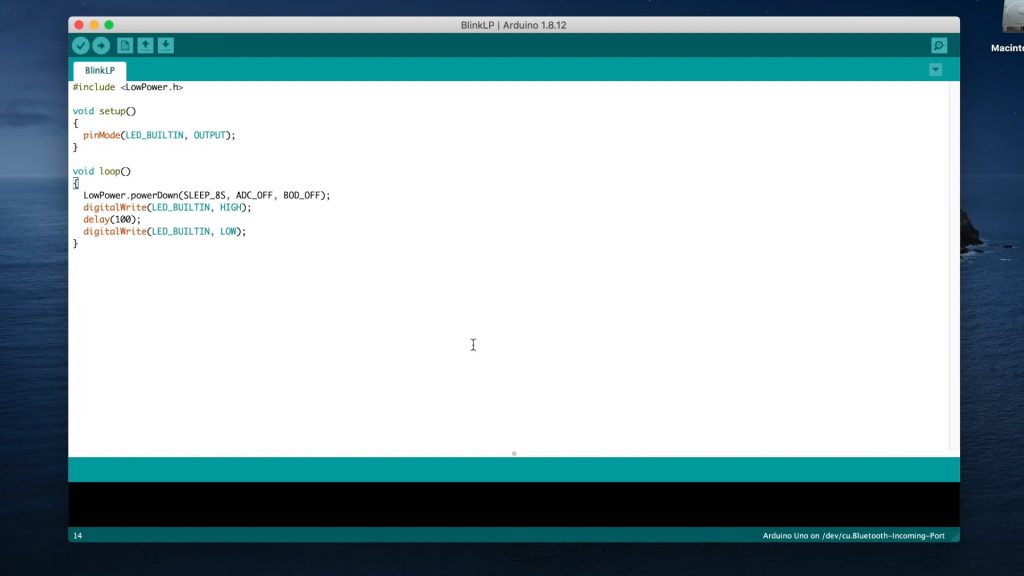

I adapted the code from the obstacle avoiding robot to use the data from the Huskylens to follow a black line drawn on the floor using the Huskylens Line Tracking example by Angelo Qiao. There are some functions that have been carried over from the obstacle avoiding robot that are not used in this code but might be useful for future adaptations.

//The DIY Life

//Michael Klements

//16/04/2021

//Huskylens Line Tracking Robot

//Adapted from Huskylens Line Tracking example by By [Angelo qiao](Angelo.qiao@dfrobot.com)

#include "HUSKYLENS.h" //Import the required libraries

#include "SoftwareSerial.h"

#include "PIDLoop.h"

#include <AFMotor.h>

AF_DCMotor rightBack(1); //Create an object to control each motor

AF_DCMotor rightFront(2);

AF_DCMotor leftFront(3);

AF_DCMotor leftBack(4);

byte motorSpeed = 60; //The maximum motor speed

int motorOffset = 15; //Factor to account for one side being more powerful

int turnSpeed = 50; //Amount to add to motor speed when turning

int leftSpeed = 0; //Variables to keep current left and right motor speeds

int rightSpeed = 0;

PIDLoop headingLoop(120, 0, 0, false); //Set up PID control for the heading, only P used for now

HUSKYLENS huskylens; //Create a Huskeylens object

int ID1 = 1; //We're tracking recognised object 1

void printResult(HUSKYLENSResult result);

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(115200); //Start serial communication

Wire.begin(); //Begin communication with the Huskeylens

while (!huskylens.begin(Wire))

{

Serial.println(F("Begin failed!"));

Serial.println(F("1.Please recheck the \"Protocol Type\" in HUSKYLENS (General Settings>>Protol Type>>I2C)"));

Serial.println(F("2.Please recheck the connection."));

delay(100);

}

huskylens.writeAlgorithm(ALGORITHM_LINE_TRACKING); //Switch the algorithm to line tracking.

rightBack.setSpeed(0); //Set the motors to the motor speed, initially all 0

rightFront.setSpeed(0);

leftFront.setSpeed(0);

leftBack.setSpeed(0);

moveForward(); //Start the motors

accelerate(); //Accelerate to the set motor speed

}

void loop()

{

int32_t error;

if (!huskylens.request(ID1)) //If a connection is not established

{

Serial.println(F("Check connection to Huskeylens"));

leftSpeed = 0;

rightSpeed = 0;

}

else if(!huskylens.isLearned()) //If an object has not been learned

{

Serial.println(F("No object has been learned"));

leftSpeed = 0;

rightSpeed = 0;

}

else if(!huskylens.available()) //If there is no arrow being shown on the screen yet

Serial.println(F("No arrow on the screen yet"));

else //Once a line is detected and an arrow shown

{

HUSKYLENSResult result = huskylens.read(); //Read and display the result

printResult(result);

error = (int32_t)result.xTarget - (int32_t)160; //Calculate the tracking error

headingLoop.update(error); //Perform PID control on the error

leftSpeed = headingLoop.m_command; //Get the left side speed change

rightSpeed = -headingLoop.m_command; //Get the right side speed change

leftSpeed += motorSpeed; //Calculate the total left side speed

rightSpeed += (motorSpeed-motorOffset); //Calculate the total right side speed

}

Serial.println(String()+leftSpeed+","+rightSpeed);

leftFront.setSpeed(leftSpeed); //Set the new motor speeds

leftBack.setSpeed(leftSpeed);

rightFront.setSpeed(rightSpeed);

rightBack.setSpeed(rightSpeed);

}

void accelerate() //Function to accelerate the motors from 0 to full speed

{

for (int i=0; i<motorSpeed; i++) //Loop from 0 to full speed

{

rightBack.setSpeed(i); //Set the motors to the current loop speed

rightFront.setSpeed(i);

leftFront.setSpeed(i+motorOffset);

leftBack.setSpeed(i+motorOffset);

delay(10);

}

}

void decelerate() //Function to decelerate the motors from full speed to zero

{

for (int i=motorSpeed; i!=0; i--) //Loop from full speed to 0

{

rightBack.setSpeed(i); //Set the motors to the current loop speed

rightFront.setSpeed(i);

leftFront.setSpeed(i+motorOffset);

leftBack.setSpeed(i+motorOffset);

delay(10);

}

}

void moveForward() //Set all motors to run forward

{

rightBack.run(FORWARD);

rightFront.run(FORWARD);

leftFront.run(FORWARD);

leftBack.run(FORWARD);

}

void stopMove() //Set all motors to stop

{

rightBack.run(RELEASE);

rightFront.run(RELEASE);

leftFront.run(RELEASE);

leftBack.run(RELEASE);

}

void turnLeft(int duration) //Set motors to turn left for the specified duration then continue

{

rightBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+turnSpeed); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+turnSpeed);

leftFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset+turnSpeed);

leftBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset+turnSpeed);

rightBack.run(FORWARD);

rightFront.run(FORWARD);

leftFront.run(BACKWARD);

leftBack.run(BACKWARD);

delay(duration);

rightBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed);

leftFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset);

leftBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset);

moveForward();

}

void turnRight(int duration) //Set motors to turn right for the specified duration then continue

{

rightBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+turnSpeed); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+turnSpeed);

leftFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset+turnSpeed);

leftBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset+turnSpeed);

rightBack.run(BACKWARD);

rightFront.run(BACKWARD);

leftFront.run(FORWARD);

leftBack.run(FORWARD);

delay(duration);

rightBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed);

leftFront.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset);

leftBack.setSpeed(motorSpeed+motorOffset);

moveForward();

}

void printResult(HUSKYLENSResult result) //Display the results on the serial monitor

{

if (result.command == COMMAND_RETURN_BLOCK)

{

Serial.println(String()+F("Block:xCenter=")+result.xCenter+F(",yCenter=")+result.yCenter+F(",width=")+result.width+F(",height=")+result.height+F(",ID=")+result.ID);

}

else if (result.command == COMMAND_RETURN_ARROW)

{

Serial.println(String()+F("Arrow:xOrigin=")+result.xOrigin+F(",yOrigin=")+result.yOrigin+F(",xTarget=")+result.xTarget+F(",yTarget=")+result.yTarget+F(",ID=")+result.ID);

}

else

{

Serial.println("Object unknown!");

}

}Let’s upload the code and see how well it works.

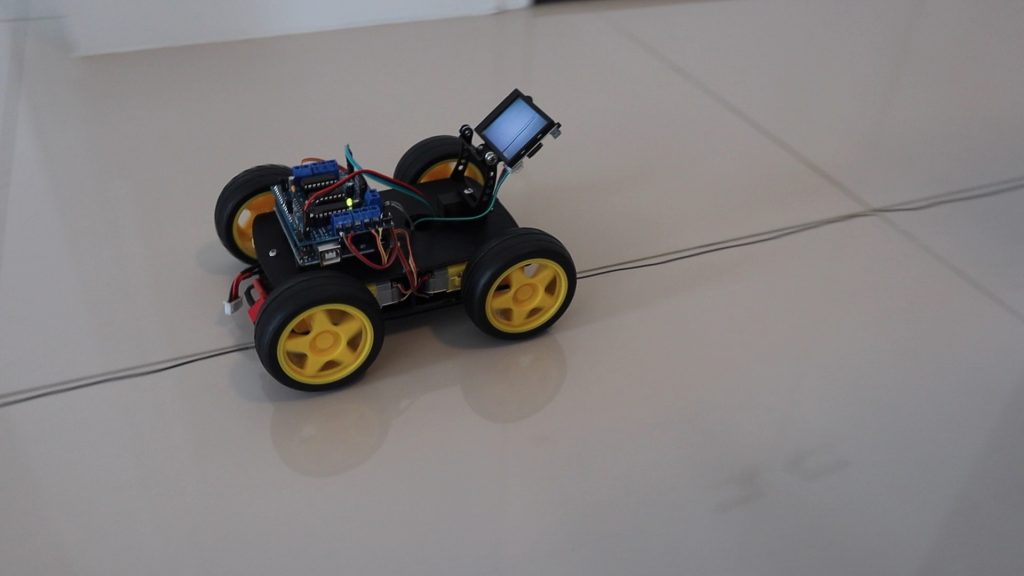

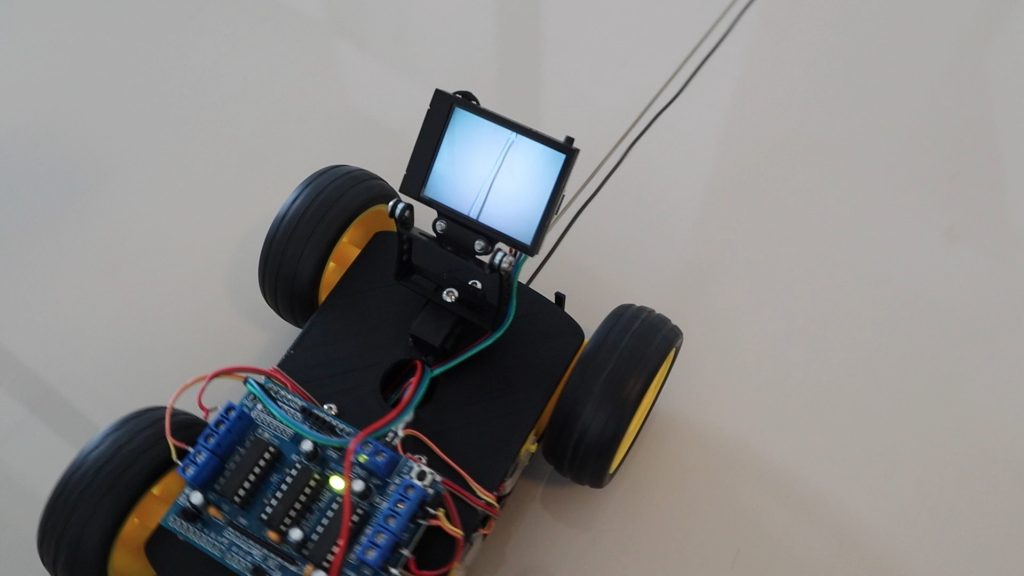

I’ll start by pointing the Huskylens on the front of the car downward so that it’s looking at the ground just ahead of the car.

I’ve drawn lines on the floor, trying to keep near the grout lines in the tiles so that it hopefully doesn’t get confused. I’ve also put some masking tape on the lines leading away from the turns so that it follows the turns and ignores the grout lines leading on from the turn.

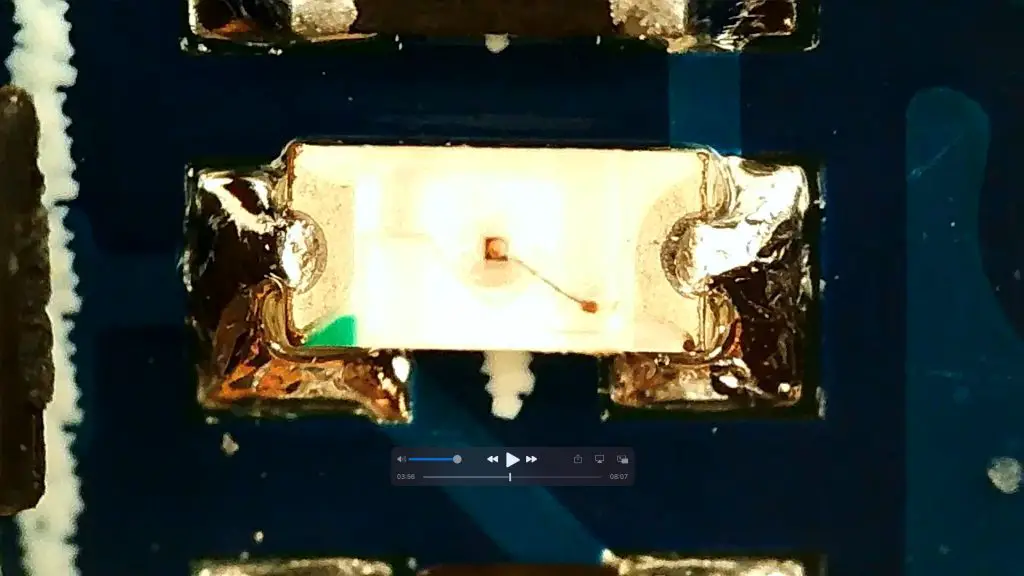

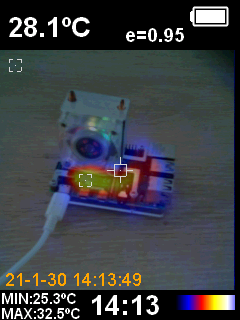

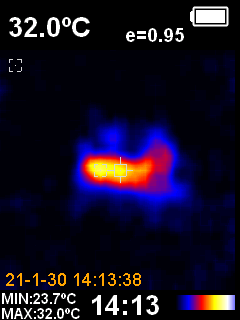

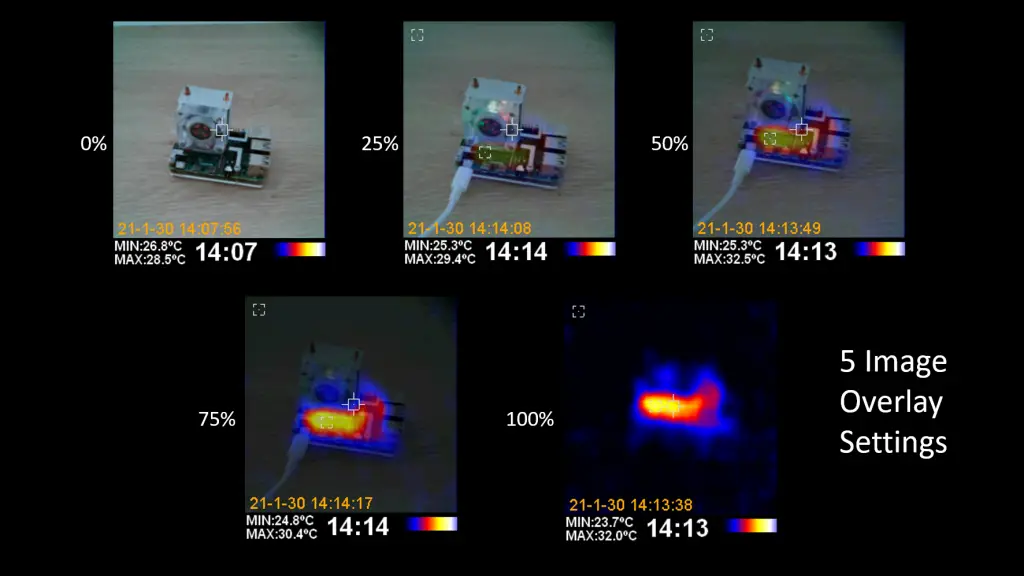

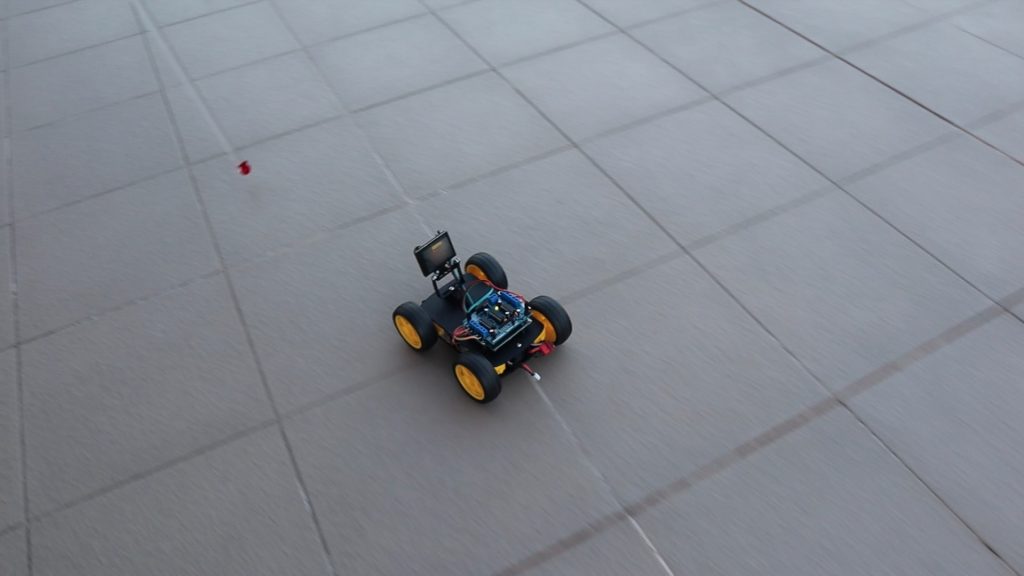

Here are some images of the car following the line. It’s best to watch the video at the begining of the guide to see the line tracking feature running.

Overall, the line tracking feature worked pretty well. The Huskylens is responsive enough that the car starts making adjustments to its direction as soon as the line starts drifting off centre or changes direction, so it’s able to track the line with a bit of speed as well. It only veered off course a couple of times during testing and these all occurred when the wheels slipped on the smooth tiled floor.

The limitation to the speed is probably more to do with the actual motors than with the Huskylens. These geared motors are really cheap and low quality, so the driver has a hard time controlling the speed accurately.

Experimenting With Object Tracking

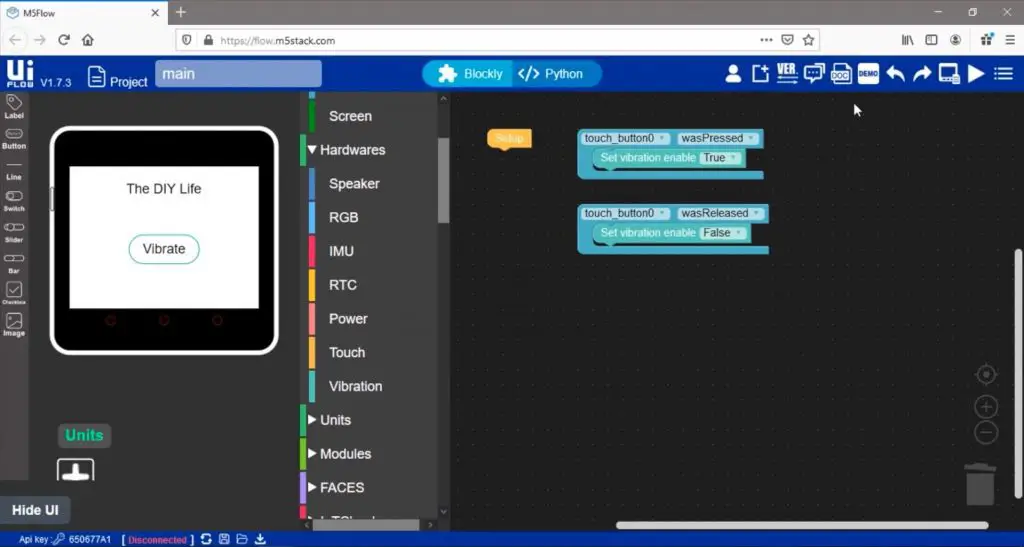

Now that we’ve tried out line tracking, let’s try object tracking.

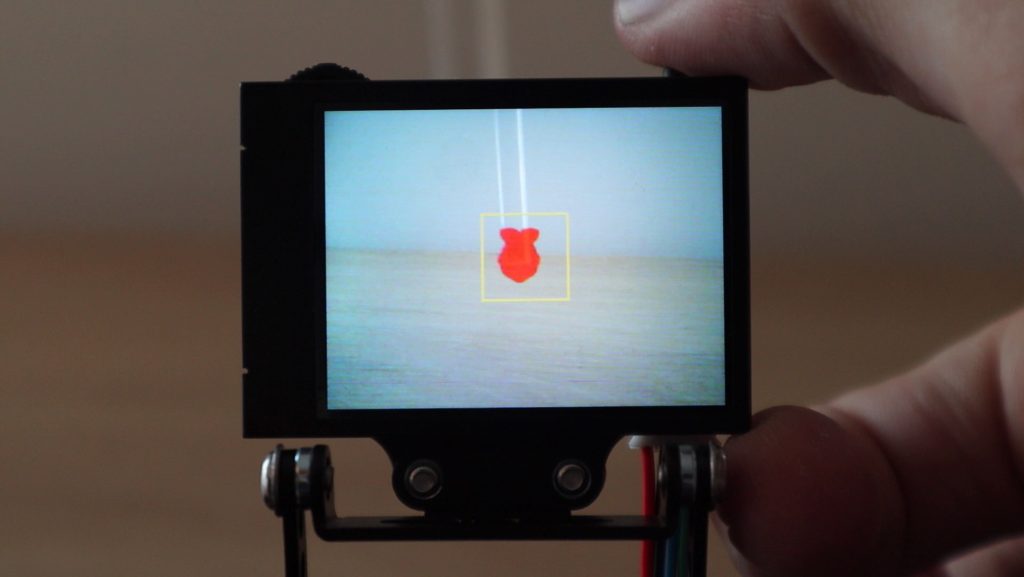

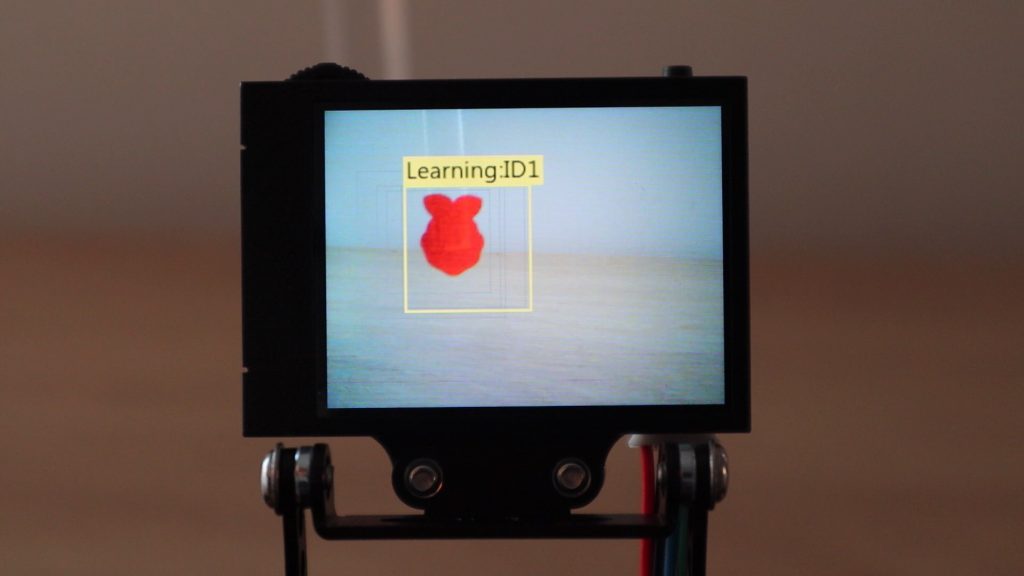

We use the selector to change over to Object Tracking mode. In this mode, the crosshair on the display is replaced by a yellow box. To start, you need to align the object you’re going to be tracking with this box and then press the learn button.

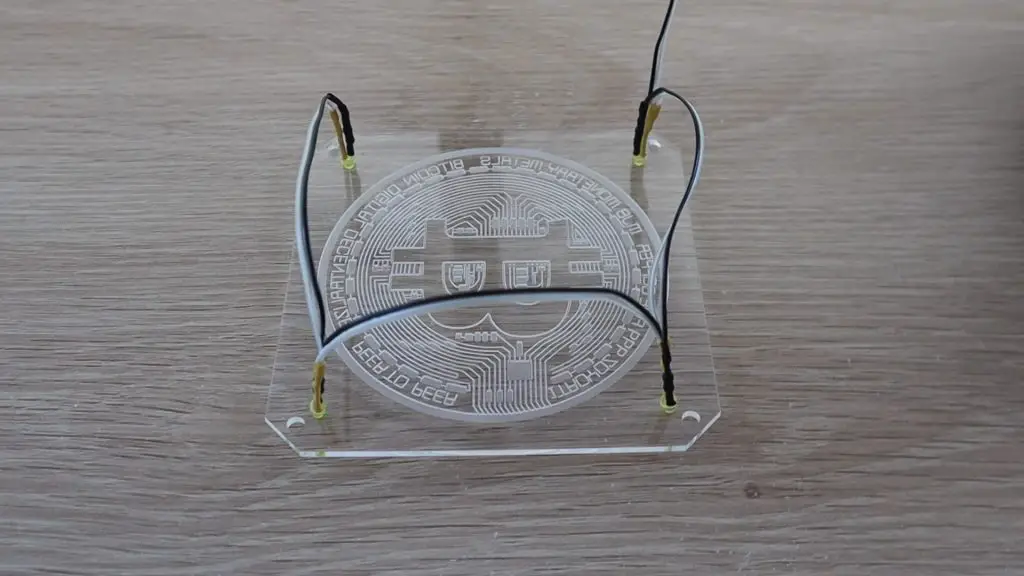

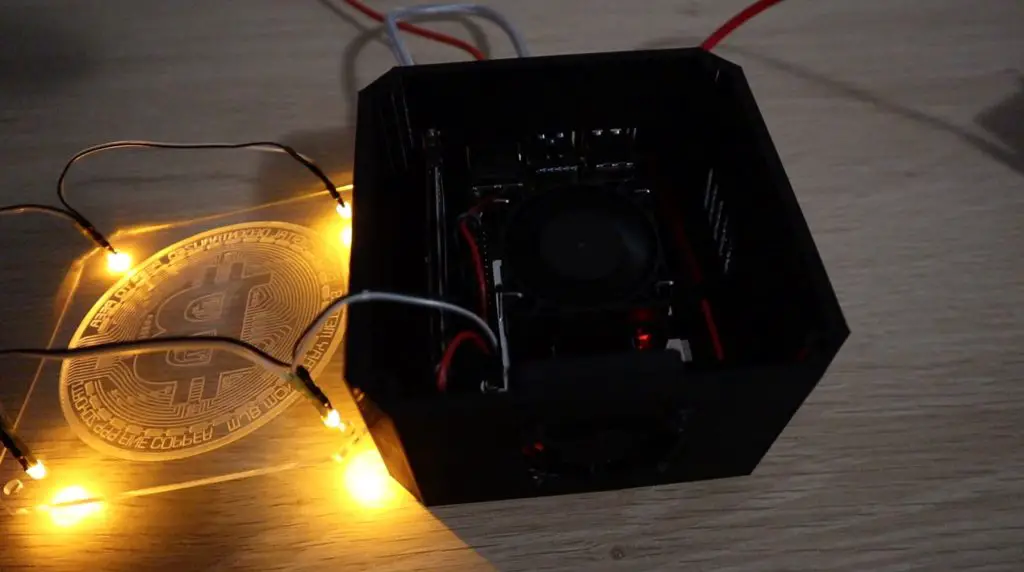

I’m going to try and use this Raspberry Pi logo cutout on a clear piece of acrylic as the object to track.

Once the object is learnt, it’ll receive an ID tag and it’ll then be followed around the display surrounded by the box. It also gets bigger or smaller if you move it closer and further away from the camera.

We’re going to use this box to control the car as well. When the box moves to the left or right of the display then we’ll move the car left or right and when it gets further away, the box gets smaller, and we’ll then move the car forward to follow the object.

I’ve adapted my old robot car code again, this time to follow the box around the screen.

//The DIY Life

//Michael Klements

//16/04/2021

//HuskyLens Object Tracking Robot

#include "HUSKYLENS.h" //Import the required libraries

#include "SoftwareSerial.h"

#include <AFMotor.h>

AF_DCMotor rightBack(1); //Create an object to control each motor

AF_DCMotor rightFront(2);

AF_DCMotor leftFront(3);

AF_DCMotor leftBack(4);

byte maxMotorSpeed = 50; //The normal motor speed

int motorOffset = 25; //Factor to account for one side being more powerful

int objectWidth = 50;

int turnGain = 12;

int offCentre = 20;

int distGain = 6;

int leftLimit = 160-offCentre;

int rightLimit = 160+offCentre;

int leftSp = 0;

int rightSp = 0;

bool isTurning = false; //Track when turning left and right

bool isTurningLeft = true;

HUSKYLENS huskylens; //Create a new Huskeylens object

int ID1 = 1;

void printResult(HUSKYLENSResult result);

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(115200); //Start serial communication

Wire.begin(); //Connect to Huskylens

while (!huskylens.begin(Wire))

{

Serial.println(F("Begin failed!"));

Serial.println(F("1.Please recheck the \"Protocol Type\" in HUSKYLENS (General Settings>>Protol Type>>I2C)"));

Serial.println(F("2.Please recheck the connection."));

delay(100);

}

huskylens.writeAlgorithm(ALGORITHM_OBJECT_TRACKING); //Switch the algorithm to object tracking.

rightBack.setSpeed(0); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(0);

leftFront.setSpeed(0);

leftBack.setSpeed(0);

moveForward(); //Set motors to forward direction

}

void loop()

{

int32_t error;

if (!huskylens.request()) //If connection to Huskylens isn't available

Serial.println(F("Fail to request objects from HUSKYLENS!"));

else if(!huskylens.isLearned()) //If an object hasn't yet been learned

{

Serial.println(F("Object not learned!"));

setMotorSpeed (0,0);

}

else if(!huskylens.available()) //If the learned object isn't visible anymore

{

Serial.println(F("Object disappeared!"));

setMotorSpeed (0,0);

}

else //If object is being tracked

{

HUSKYLENSResult result = huskylens.read(); //Get the results of the object being tracked

if(result.xCenter < leftLimit)

{

leftSp = -turnGain*(leftLimit-result.xCenter);

rightSp = turnGain*(leftLimit-result.xCenter);

}

else if(result.xCenter > rightLimit)

{

leftSp = turnGain*(result.xCenter-rightLimit);

rightSp = -turnGain*(result.xCenter-rightLimit);

}

if(result.width < objectWidth)

{

leftSp = leftSp+(distGain*(objectWidth-result.width));

rightSp = rightSp+(distGain*(objectWidth-result.width));

}

if(leftSp > maxMotorSpeed)

leftSp = maxMotorSpeed;

else if(leftSp < 0)

leftSp = 0;

if(rightSp > maxMotorSpeed)

rightSp = maxMotorSpeed;

else if(rightSp < 0)

rightSp = 0;

setMotorSpeed (leftSp, rightSp);

leftSp = 0;

rightSp = 0;

printResult(result);

}

}

void moveForward() //Set all motors to run forward

{

rightBack.run(FORWARD);

rightFront.run(FORWARD);

leftFront.run(FORWARD);

leftBack.run(FORWARD);

}

void stopMove() //Set all motors to stop

{

rightBack.run(RELEASE);

rightFront.run(RELEASE);

leftFront.run(RELEASE);

leftBack.run(RELEASE);

}

void setMotorSpeed (int leftTempSp, int rightTempSp)

{

rightBack.setSpeed(rightTempSp); //Set the motors to the motor speed

rightFront.setSpeed(rightTempSp);

leftFront.setSpeed(leftTempSp+motorOffset);

leftBack.setSpeed(leftTempSp+motorOffset);

}

void printResult(HUSKYLENSResult result) //Display the results on the serial monitor

{

if (result.command == COMMAND_RETURN_BLOCK)

{

Serial.println(String()+F("Block:xCenter=")+result.xCenter+F(",yCenter=")+result.yCenter+F(",width=")+result.width+F(",height=")+result.height+F(",ID=")+result.ID);

}

else if (result.command == COMMAND_RETURN_ARROW)

{

Serial.println(String()+F("Arrow:xOrigin=")+result.xOrigin+F(",yOrigin=")+result.yOrigin+F(",xTarget=")+result.xTarget+F(",yTarget=")+result.yTarget+F(",ID=")+result.ID);

}

else

{

Serial.println("Object unknown!");

}

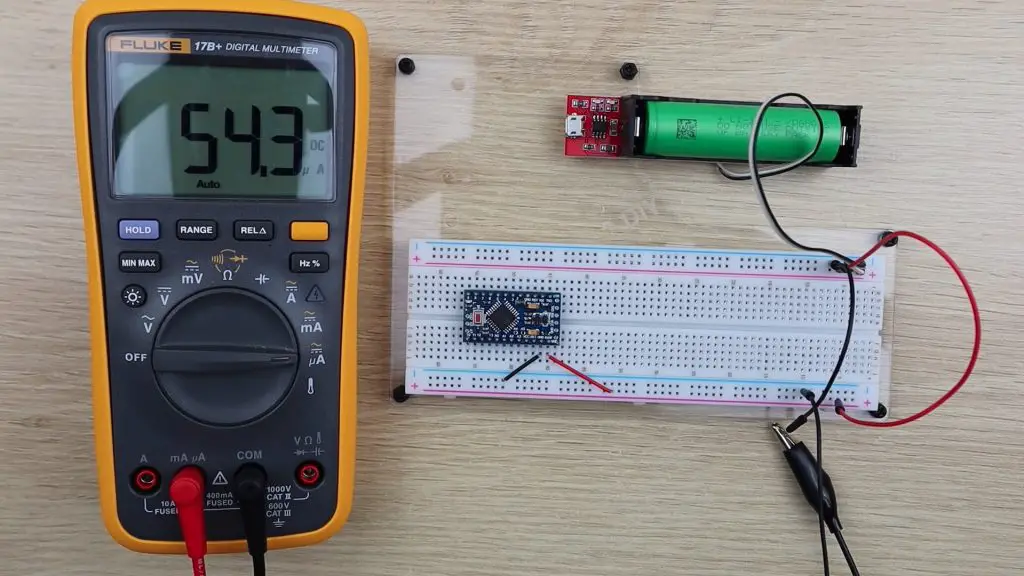

}I uploaded the code to the robot and then tried the tracking out. This example took a bit more time to set up and get to a point where it was working reasonably reliably. Most of the time was spent adjusting the gains on the turning and distance tracking as it seemed to either not respond at all or respond too aggressively.

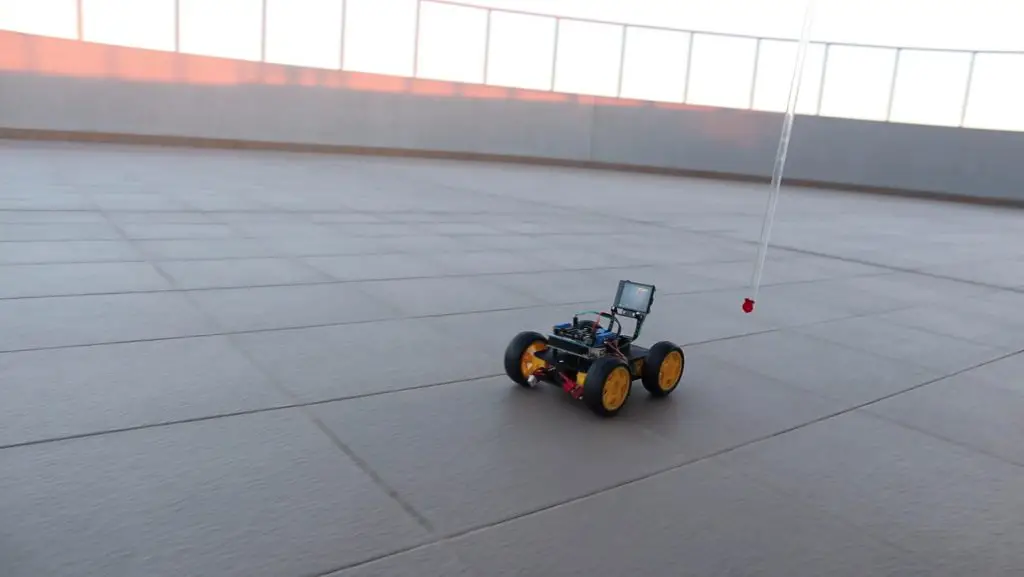

I eventually got it working reasonably well. The robot followed the Raspberry Pi logo around, moving forward when it was moved away and turning left and right to bring it back into the centre of the display.

You can watch the object tracking in the video at the beginning of this project as well.

I probably need to spend a bit more time adjusting the gains, but you get a good idea of how the object tracking works.

I’d also like to try the object tracking mode on a two axis servo mount, as I think the results would be a bit more reliable and consistent than with the car.

Let me know what you think of the Huskylens and my robot car in the comments section below.