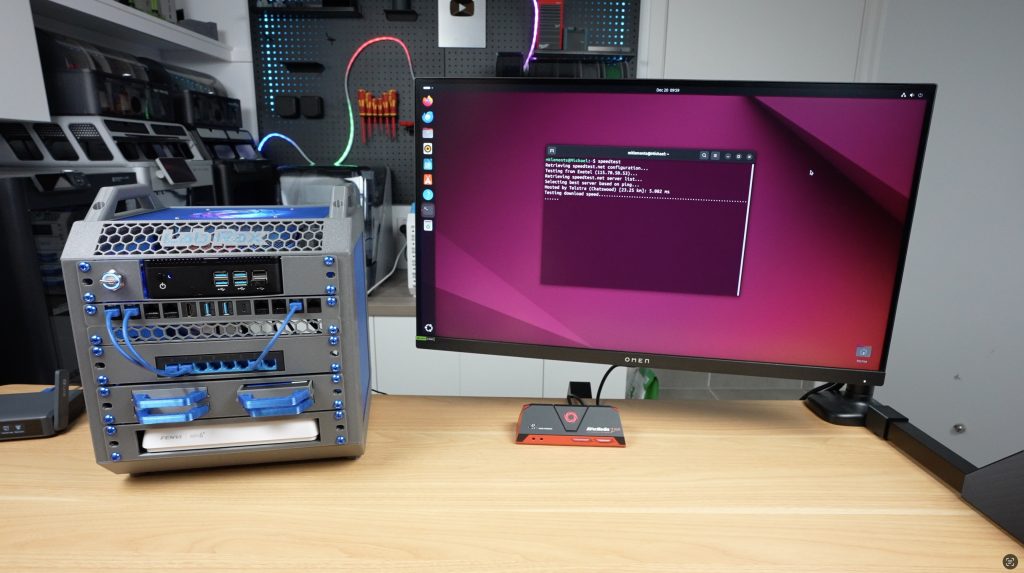

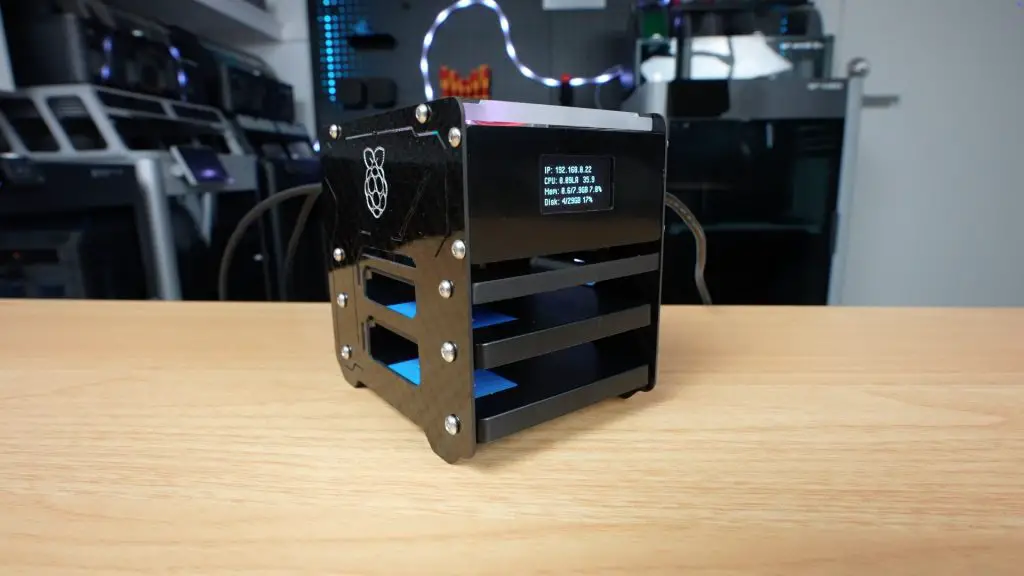

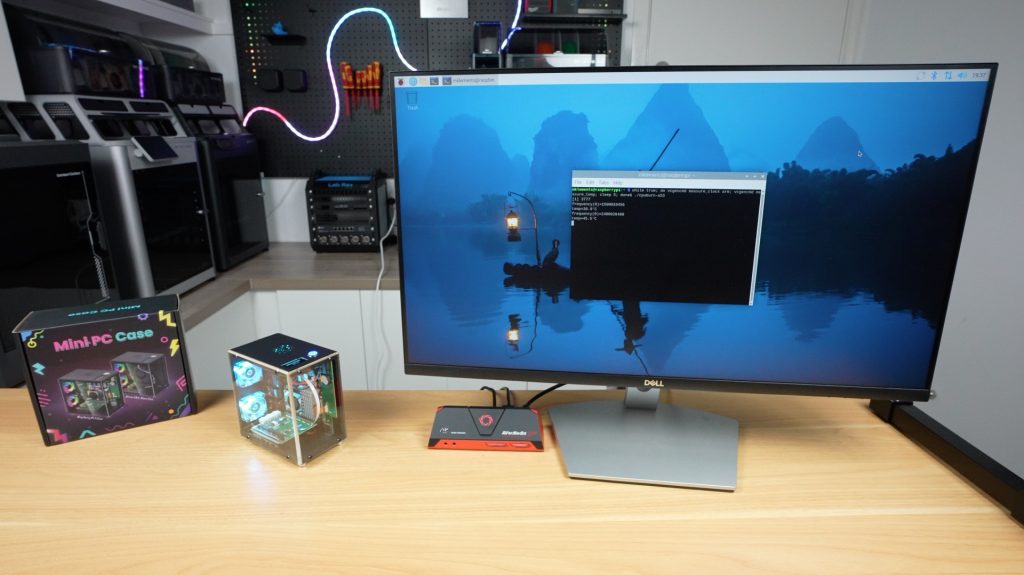

Today, we’re taking a detailed look at the Beelink ME Pro, a new two-bay NAS that packs some surprisingly unique features into an extremely compact chassis. It’s smaller than most mini PCs, offers 5 gigabit networking, includes three NVMe slots, and even features a slide-out, upgradeable motherboard. There is quite a bit going on inside this small enclosure, so in this review, we’ll take a look at the external and internal hardware, install some drives in it, and run performance testing to determine whether this compact NAS is worthy of storing your data.

Here’s my video review of the Beelink ME Pro. Read on for my written review:

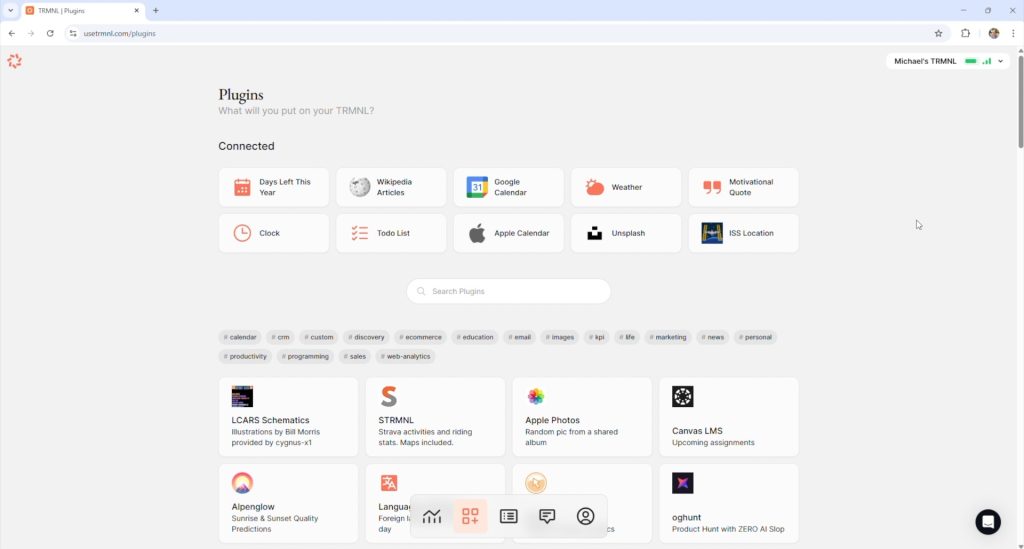

Where To Buy The Beelink ME Pro

- Beelink ME Pro (Beelink’s Amazon Store) – Buy Here

- Beelink ME Pro (Beelink’s Web Store) – Buy Here

- 2TB Crucial P3 Plus – Buy Here

- WD Red NAS Drive – Buy Here

Tools & Equipment Used

Some of the above parts are affiliate links. By purchasing products through the above links, you’ll be supporting my projects, at no additional cost to you.

Unboxing and First Impressions

Inside the box, Beelink includes a user manual, the ME Pro itself, and a separate accessories box. The accessory box includes a 120W external power brick, a network cable, an HDMI cable, and two sets of drive mounting screws, one for 3.5-inch and one for 2.5-inch drives. The NAS arrives well protected with foam inserts and plastic wrapping.

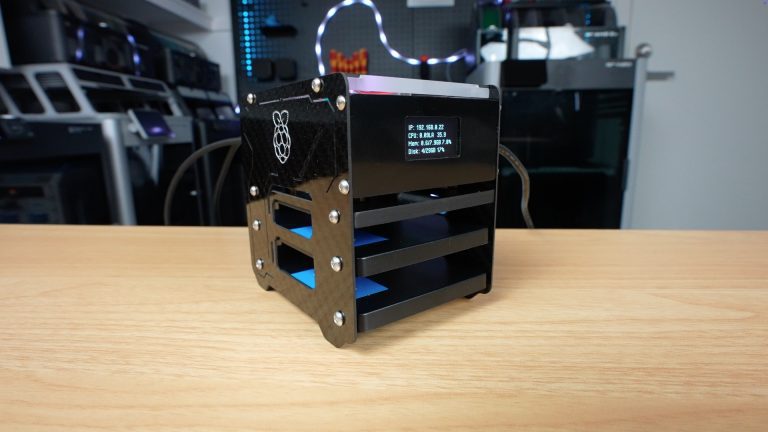

The first thing that stands out when removing the ME Pro from its packaging is its size. Measuring only 166 x 121 x 112 millimetres, it is noticeably smaller than most traditional two-bay NAS units. This compact footprint provides obvious space-saving advantages, although it also introduces some design trade-offs that will become clearer later. The chassis features an all-metal unibody construction, giving it a premium feel and a surprisingly solid weight of 1.5 kilograms when empty. In hand, it feels closer to a high-end mini PC than a typical NAS.

External Design and Connectivity

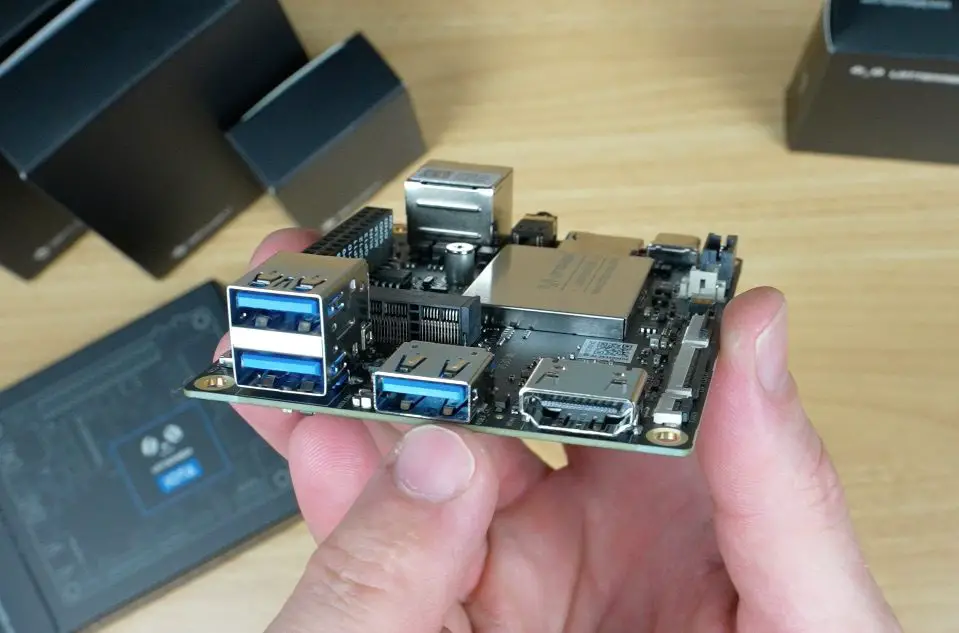

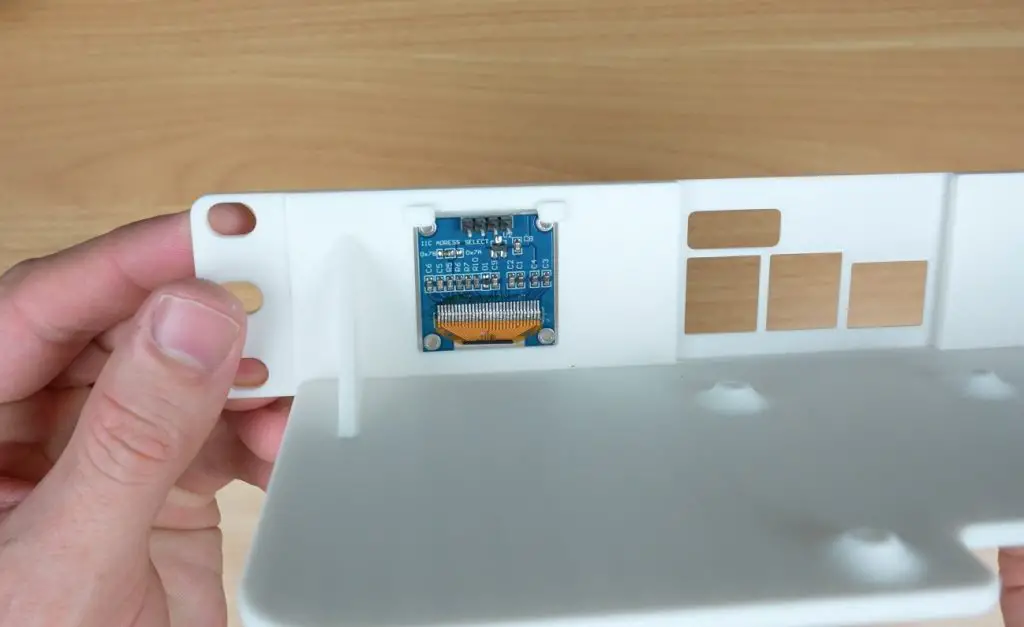

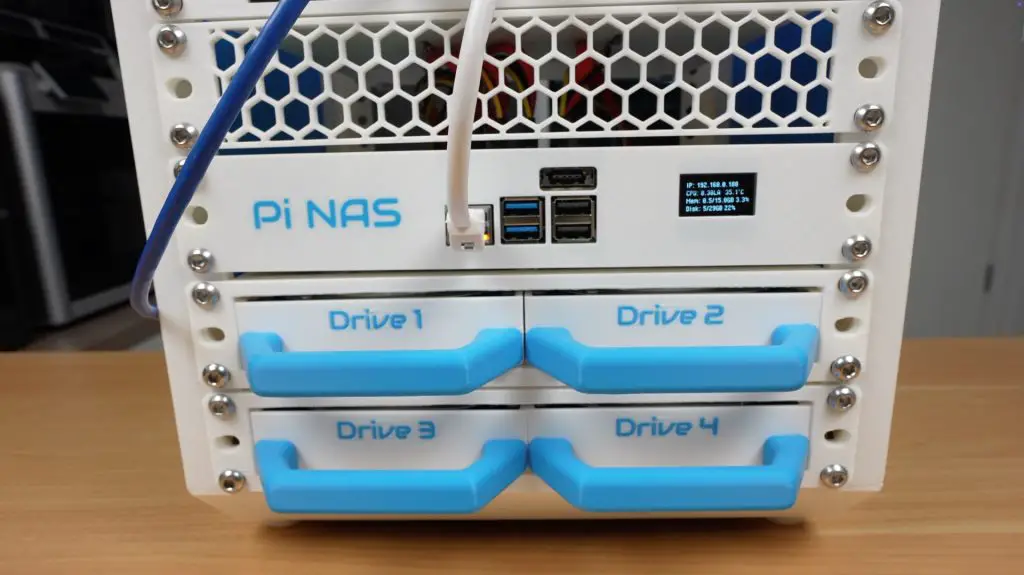

On the front of the ME Pro, we’ve got reset and clear CMOS access holes, a USB 3.2 Type-A port, and the power button. The front panel design uses a clean, retro look, a bit like a Marshall amplifier, complete with a dust-filtered grille. The top and sides don’t have any ports or interfaces on them.

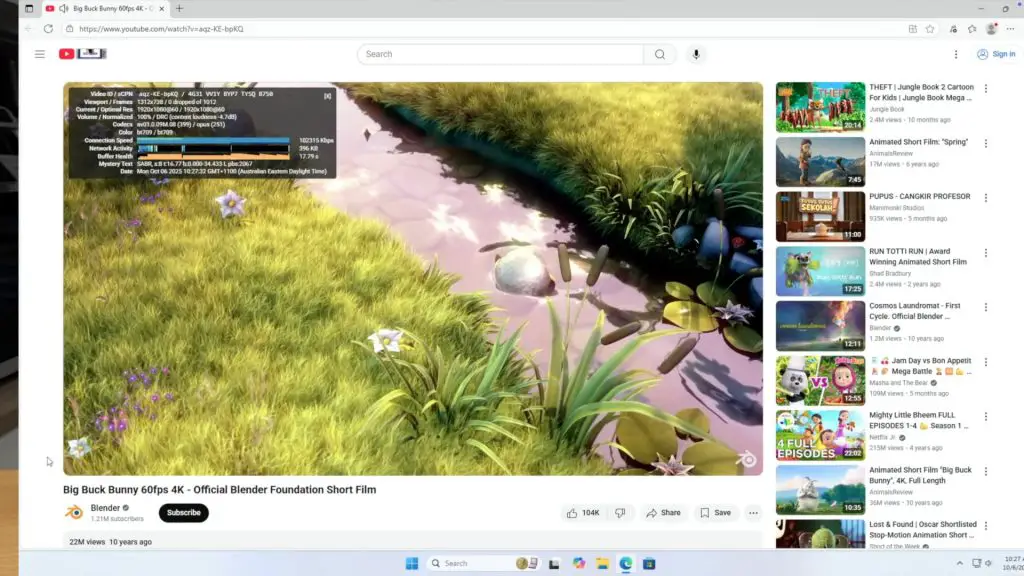

At the back, we’ve got all of the main IO. Power is supplied through a barrel jack from the external 120W power supply, which differs from some recent Beelink devices that incorporate internal power supplies. Networking is handled through two Ethernet ports, a 5-gigabit port driven by a Realtek RTL8126 controller and a 2.5-gigabit port using an Intel i226-V chip. Next to those, we’ve got an HDMI output supporting 4K at 60Hz, two USB 2.0 ports, a USB 3.2 Type-C port, and a 3.5mm headphone jack. Above those are the ventilation holes for the integrated cooler.

At the bottom we’ve got a little storage bay for the hex key for the trays and covers, which is kinda cool and useful.

With these interfaces, you can already see that this isn’t just a NAS, it’s designed to be a small home server platform.

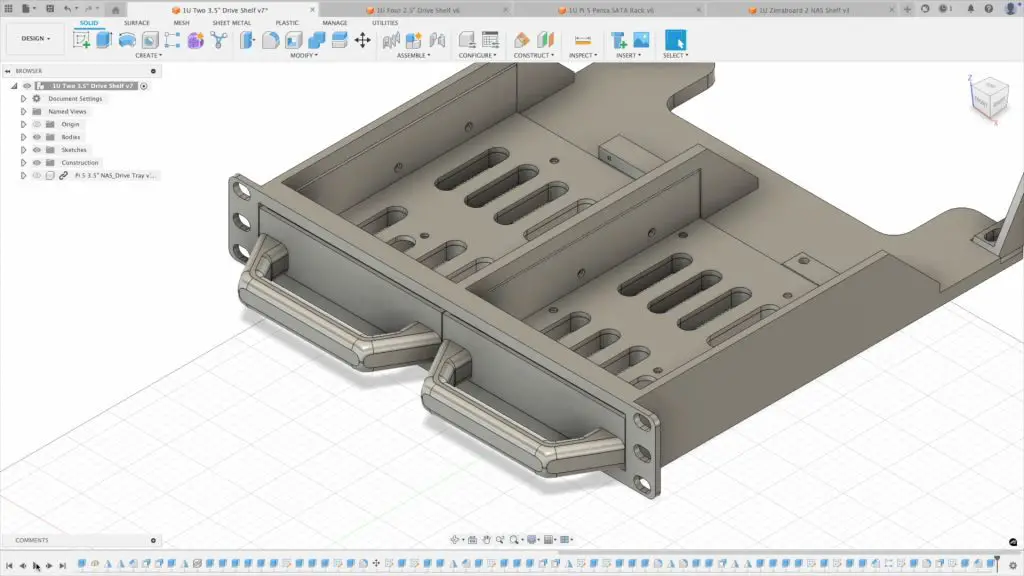

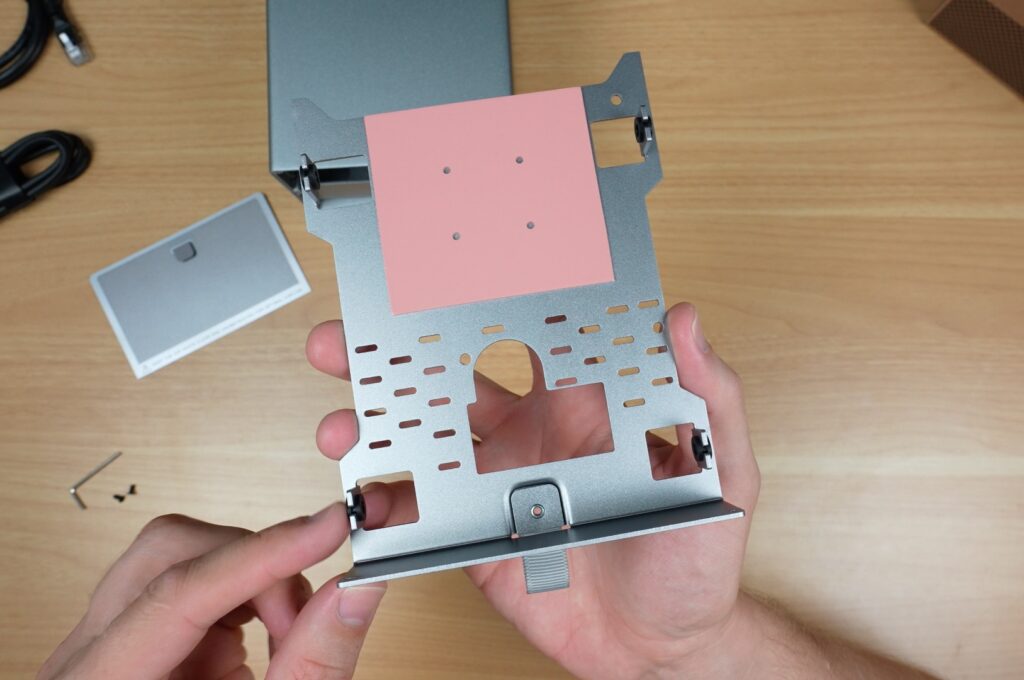

Drive Bays and Storage Design

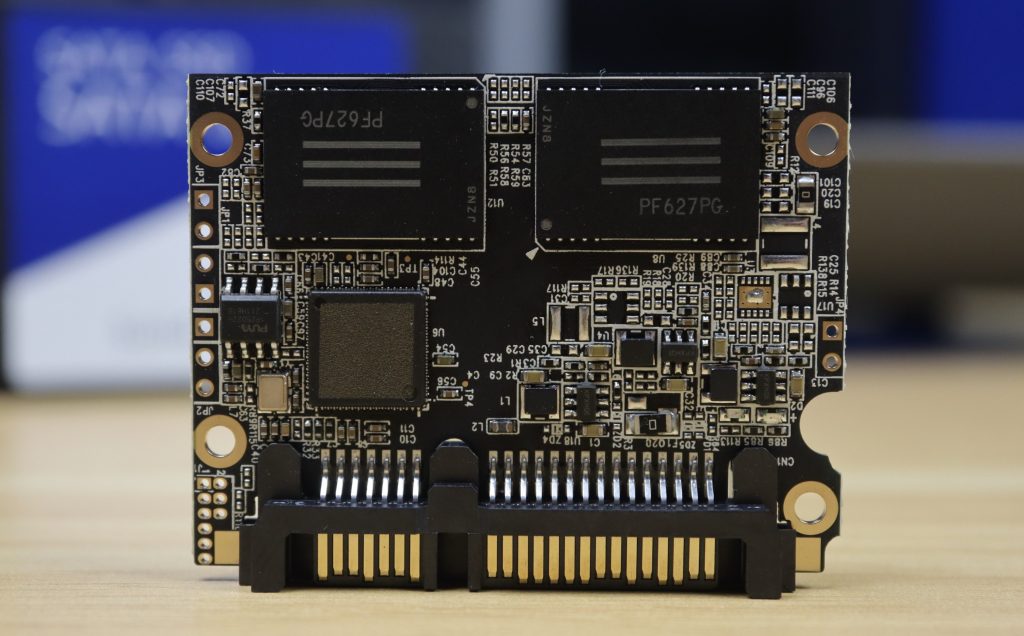

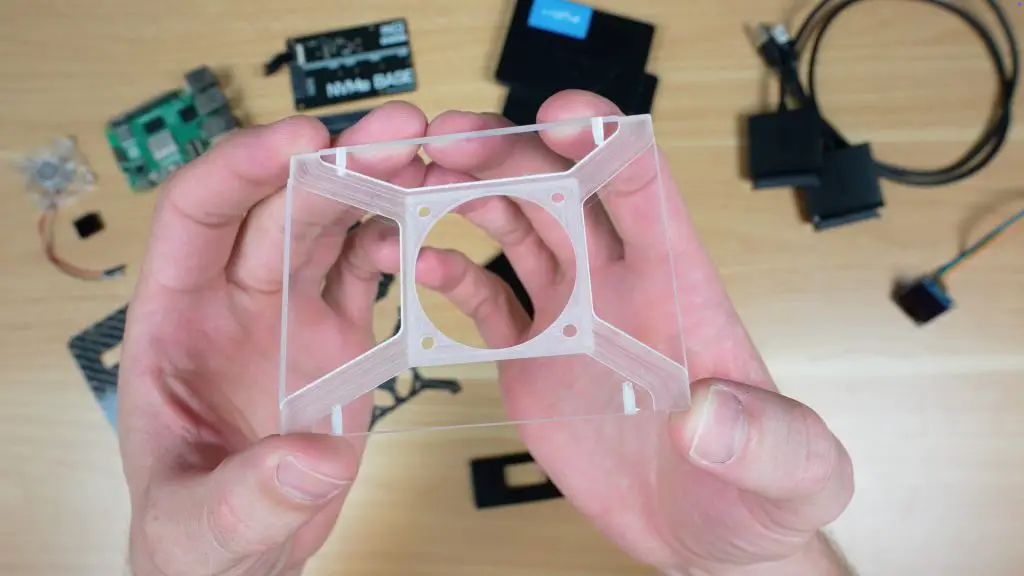

Behind the magnetic removable front grille are the two 3.5-inch drive bays. Unlike many modern NAS devices that use tool-less drive trays, Beelink has opted for a screw-mounted design. They’ve said that this approach helps reduce operating noise, which makes sense given that this unit is intended for home or desktop environments. The drive trays use dual-sided silicone plugs and mounting screws to secure drives, while also incorporating thermal pads that conduct heat away from the drive PCBs and into the chassis. This is an uncommon approach, and the first time I have seen thermal pads used directly on drive PCBs in a NAS enclosure. The trays also include mounting points for 2.5-inch SATA SSDs.

So this NAS is better suited to users who intend to install drives and forget about them for a long time, which, to be fair, is probably most users, especially on a two-bay. I’ve had my main NAS set up for 3.5 years, and I’ve never removed a drive from it.

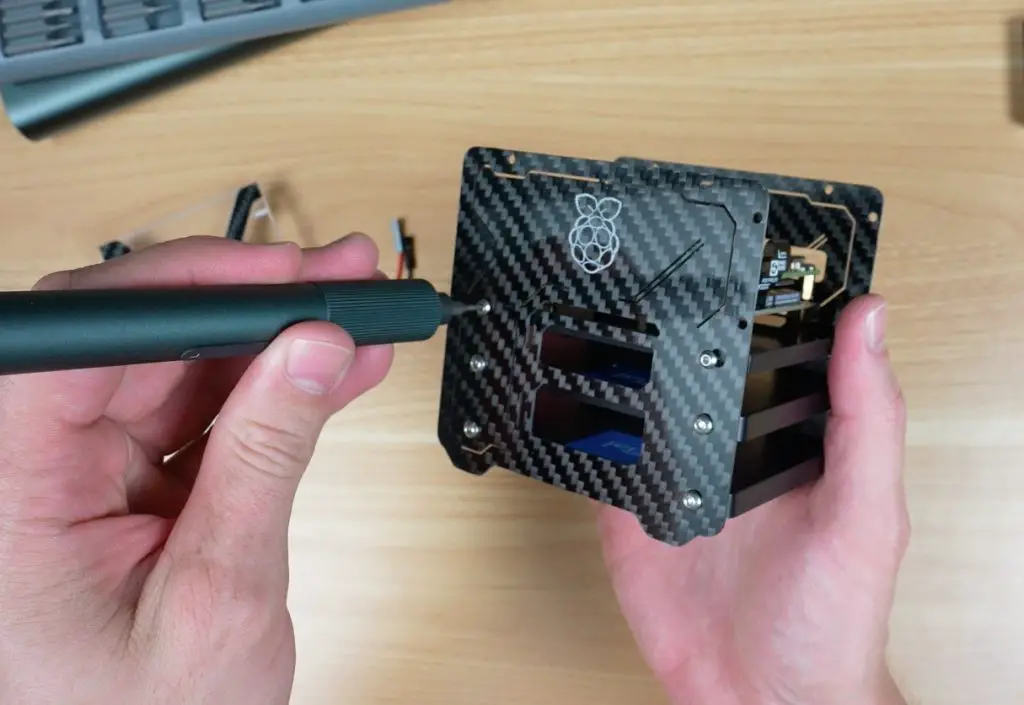

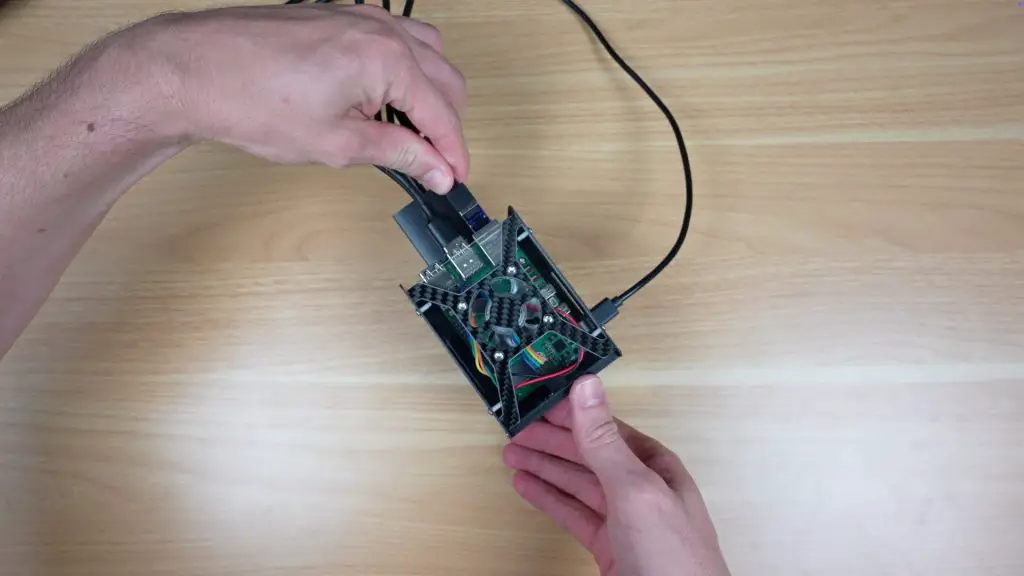

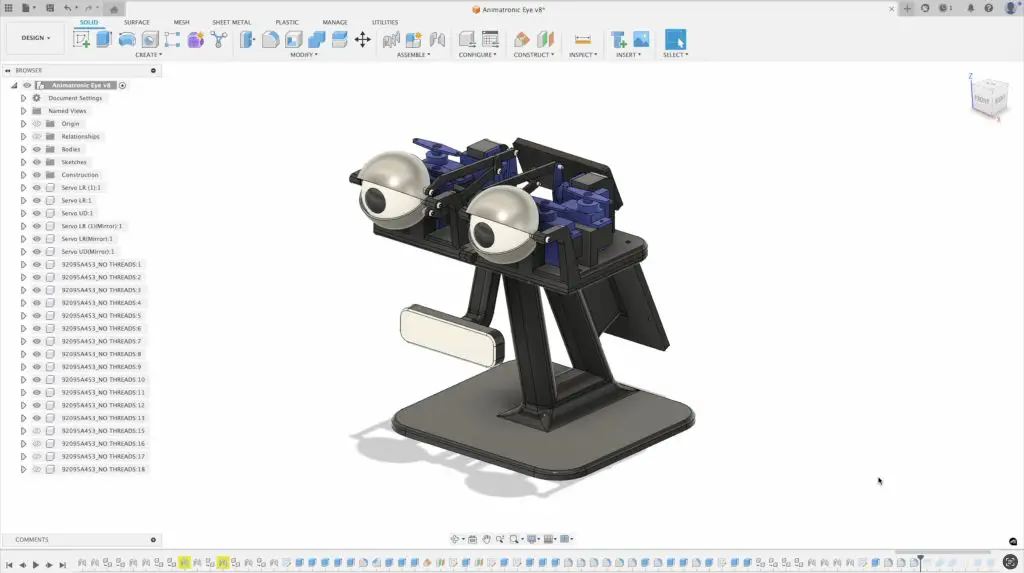

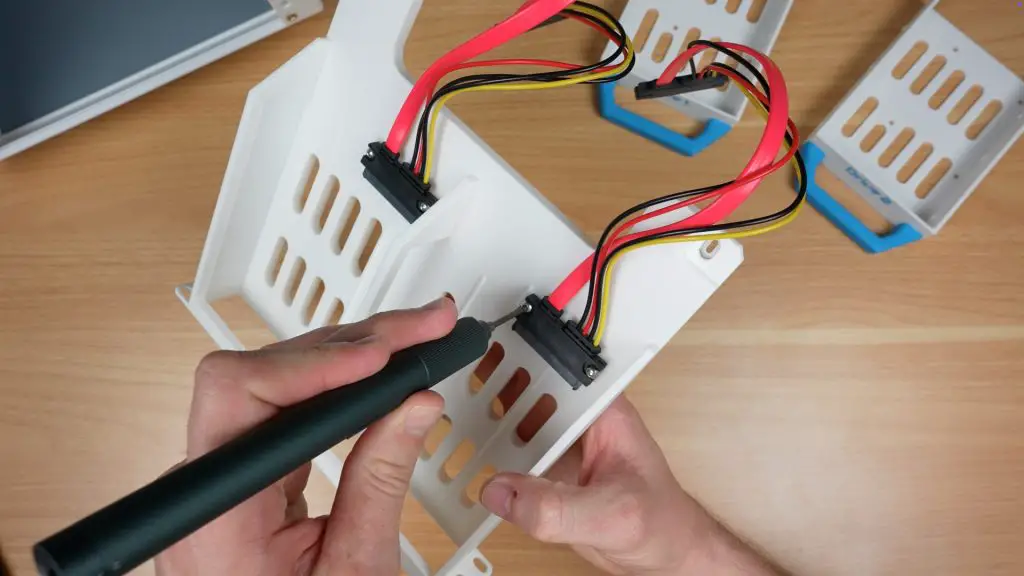

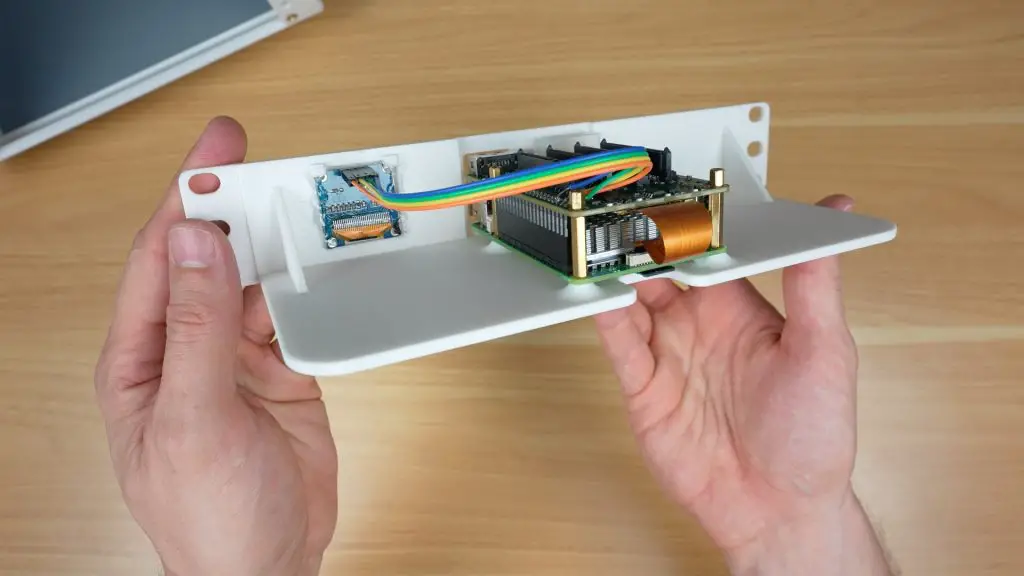

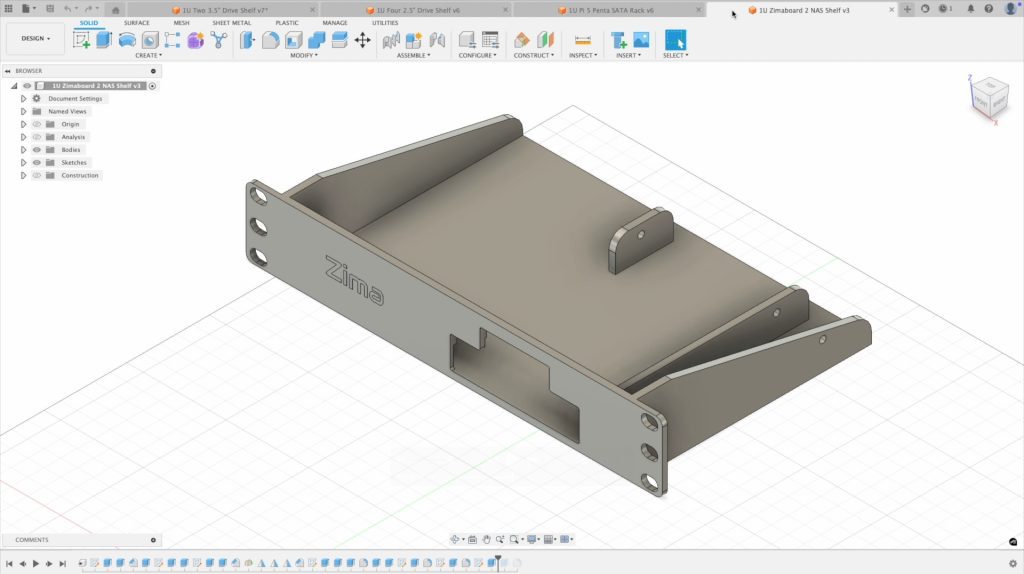

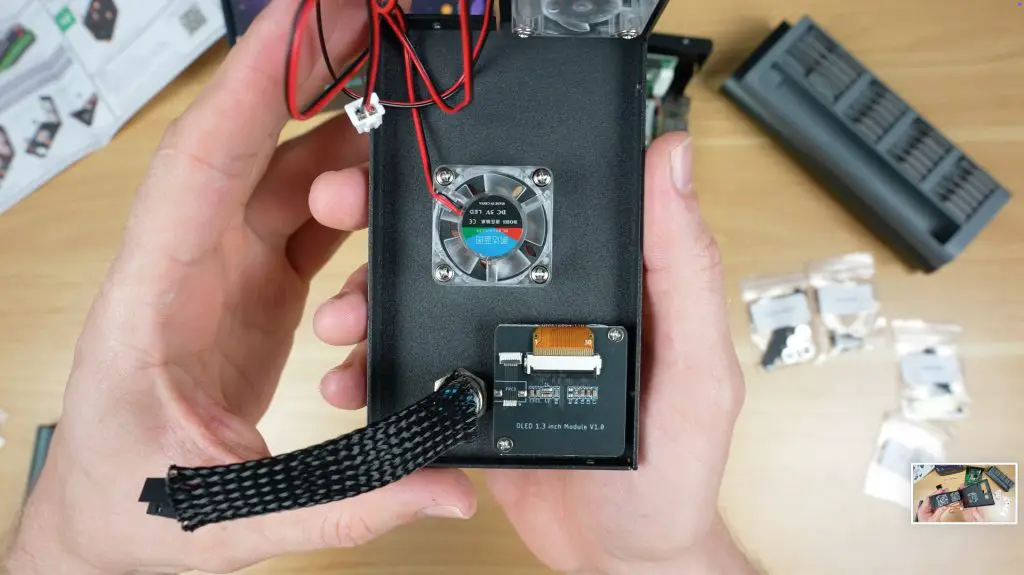

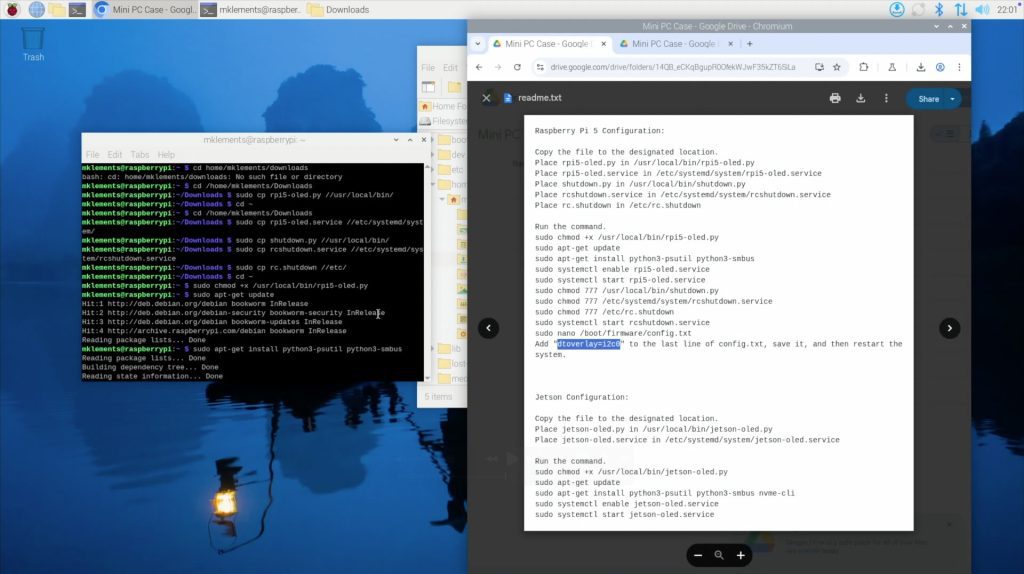

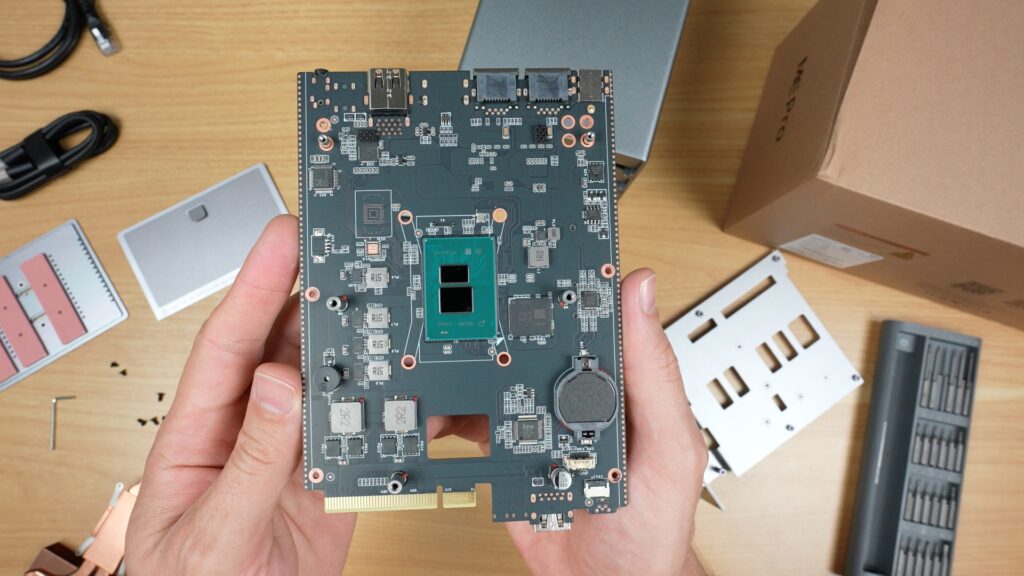

Modular Motherboard and Internal Hardware

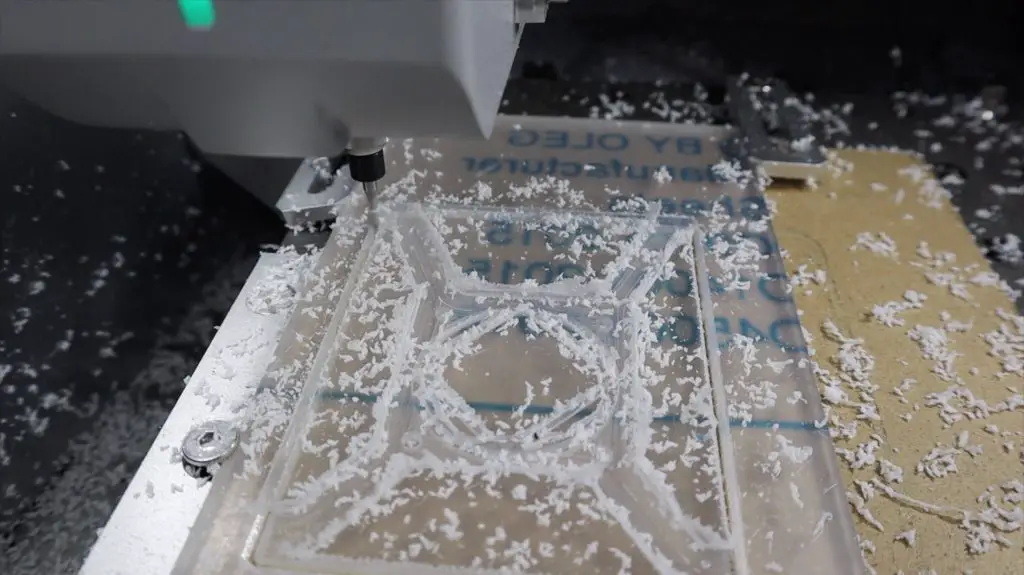

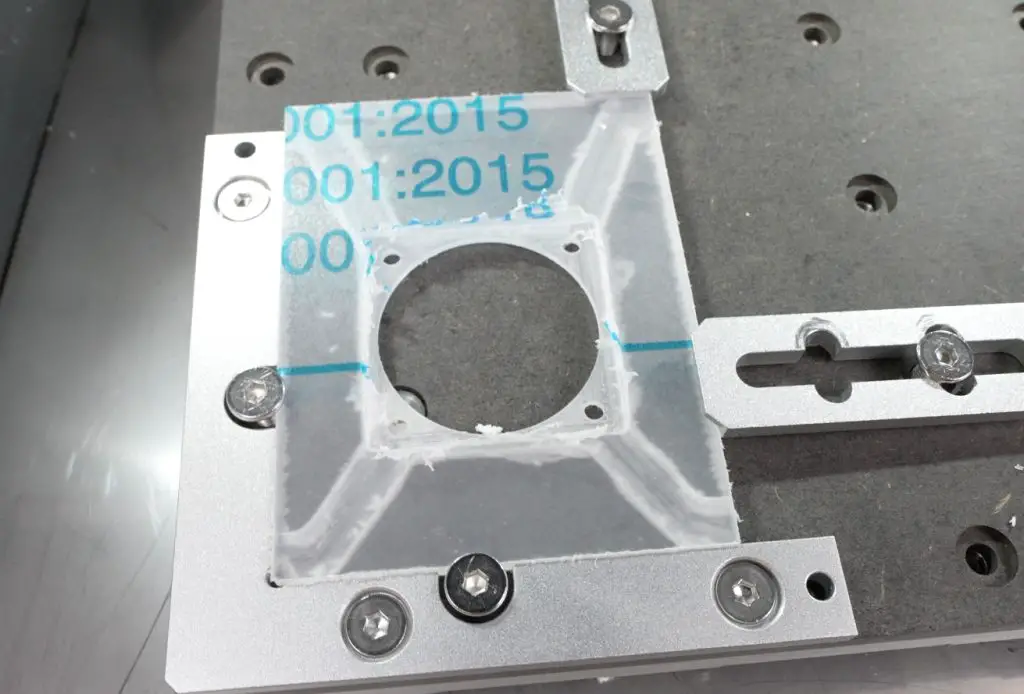

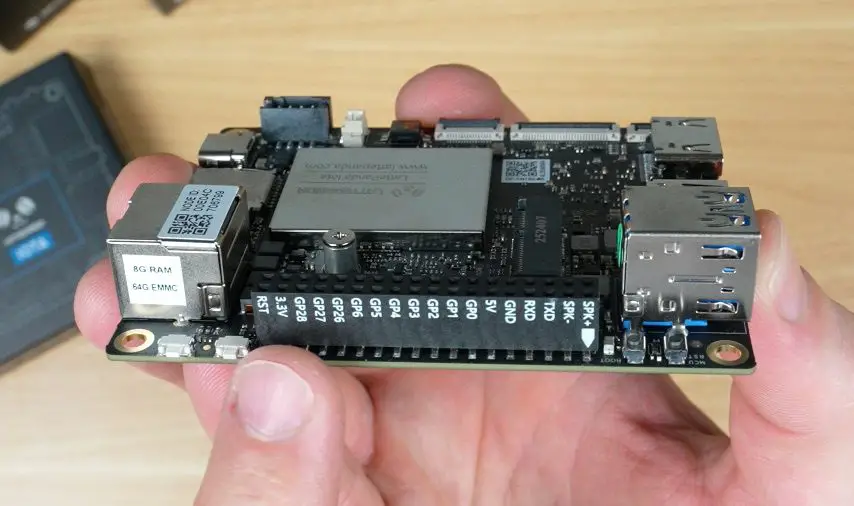

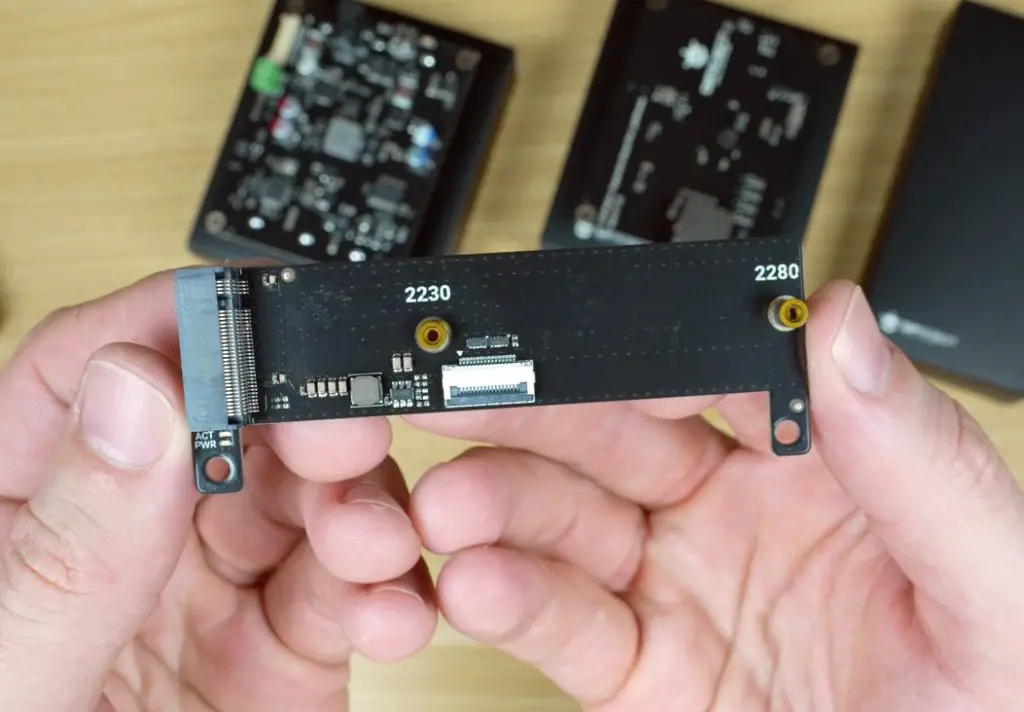

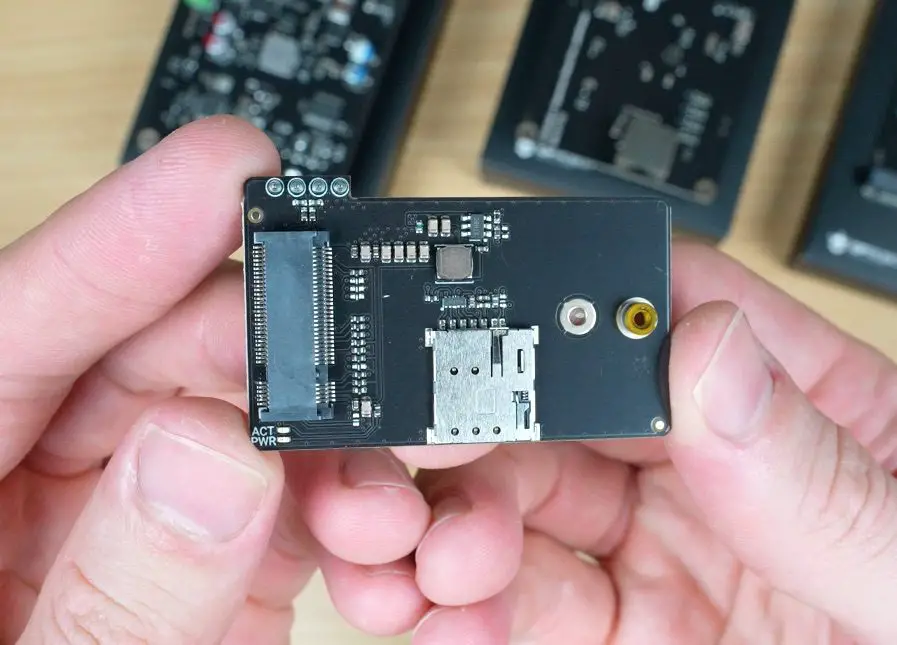

Beneath the drives, we’ve got the motherboard, which again has some unique features. By removing a couple of hex screws on the rear and bottom of the unit, the entire motherboard tray can be pulled out, providing direct access to the cooling system, CPU, and NVMe storage slots. This design simplifies cleaning, maintenance, and potential upgrades. The motherboard seems to connect to the drive backplane using a PCIe-style connector, enabling this modular approach.

Beelink has indicated plans to release additional motherboard options, including an AMD and ARM version, which is really interesting to see. I can’t think of any other NAS solutions that offer this level of modularity.

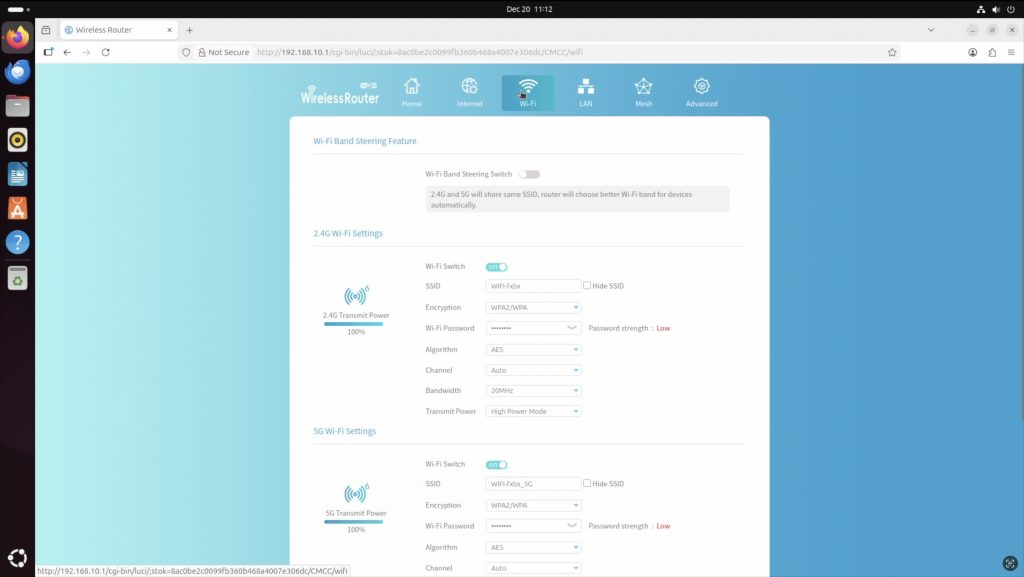

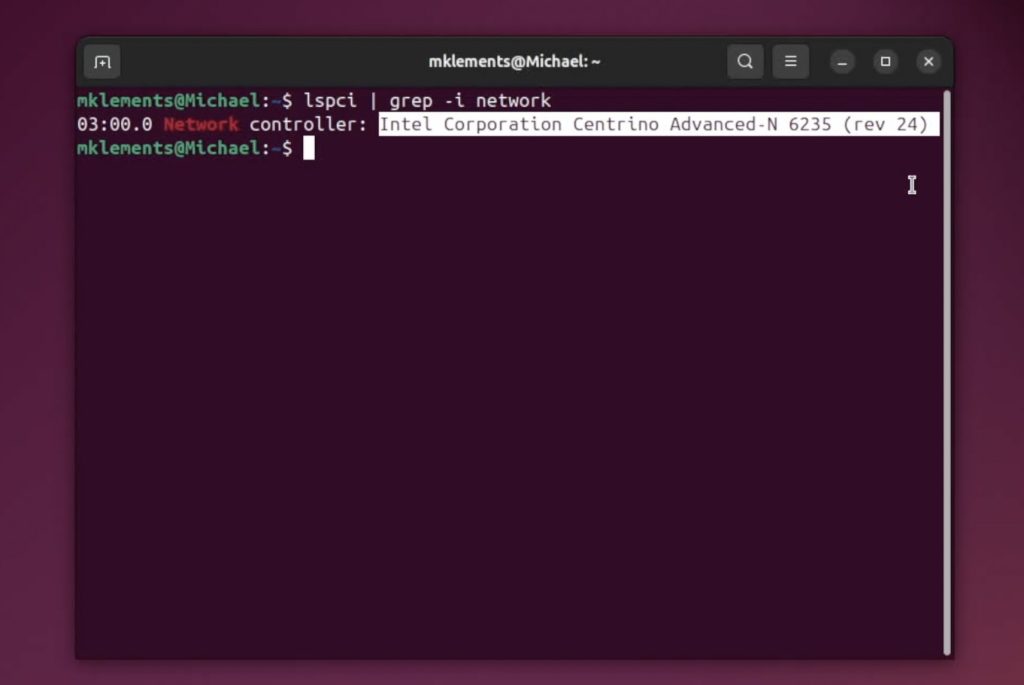

This version is equipped with an Intel Twin Lake N95 processor, paired with 12GB of LPDDR5 memory running at 4800MHz. The RAM is soldered to the motherboard and is therefore not upgradeable. The system also includes a 128GB NVMe SSD dedicated to the operating system. The N95 processor provides four cores running at up to 3.4GHz. In addition to the wired networking options, the ME Pro has WiFi 6 and Bluetooth 5.4.

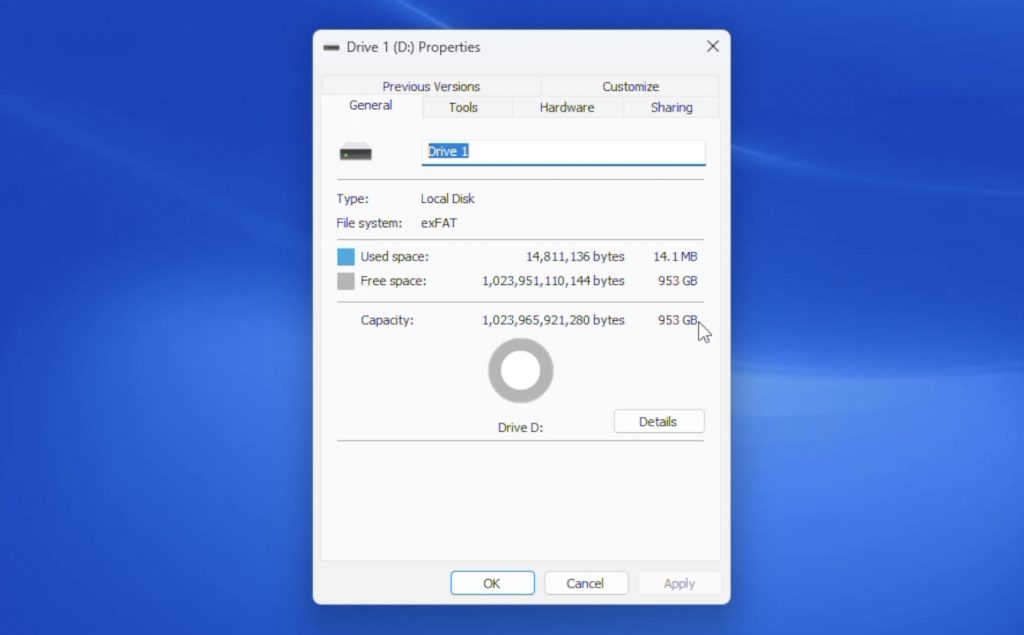

Storage expansion is handled through three M.2 NVMe slots, each supporting drives up to 4TB. One slot is occupied by the operating system drive and operates at PCIe 3.0 x 2 speeds, while the two additional storage slots run at PCIe 3.0 x 1. Combined with the two SATA bays, each capable of supporting drives up to 30TB, the system can accommodate a maximum total storage capacity of 72TB.

Cooling System

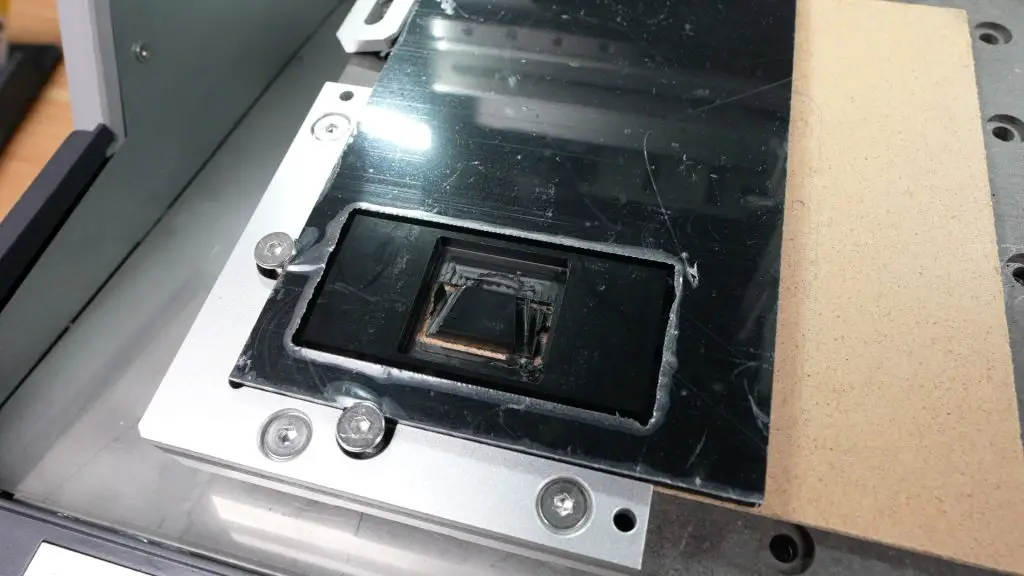

Beelink has implemented an unconventional cooling solution in the ME Pro. Instead of relying on a single rear exhaust fan, the system uses an internal blower-style fan that pushes air through a copper heat pipe cooler. The aluminium chassis itself also acts as a large heatsink. Heat generated by installed drives is transferred through thermal pads to the tray and chassis, while the blower fan draws air in across the drives and exhausts it through the heatsink and out the rear of the case.

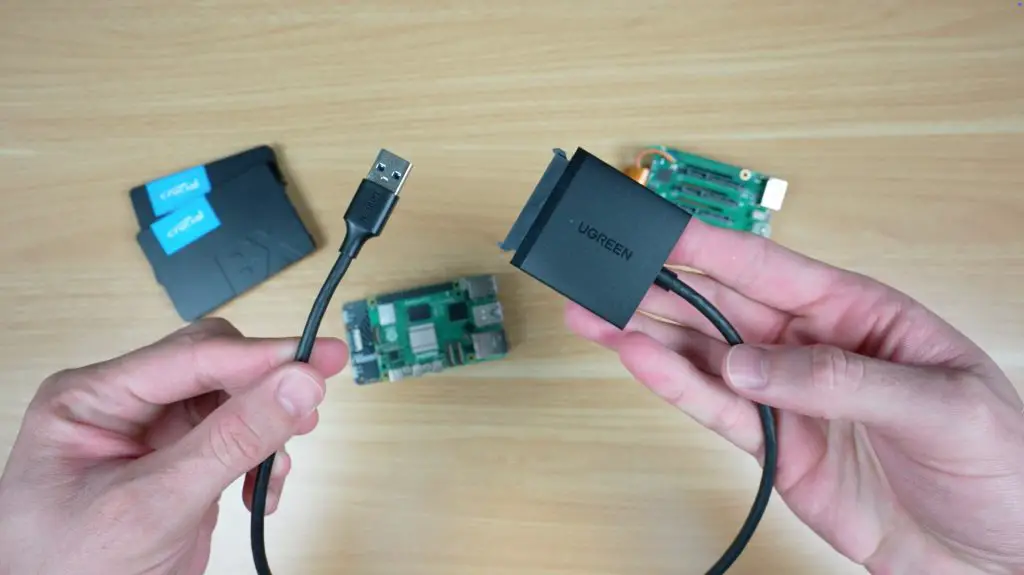

Test Setup

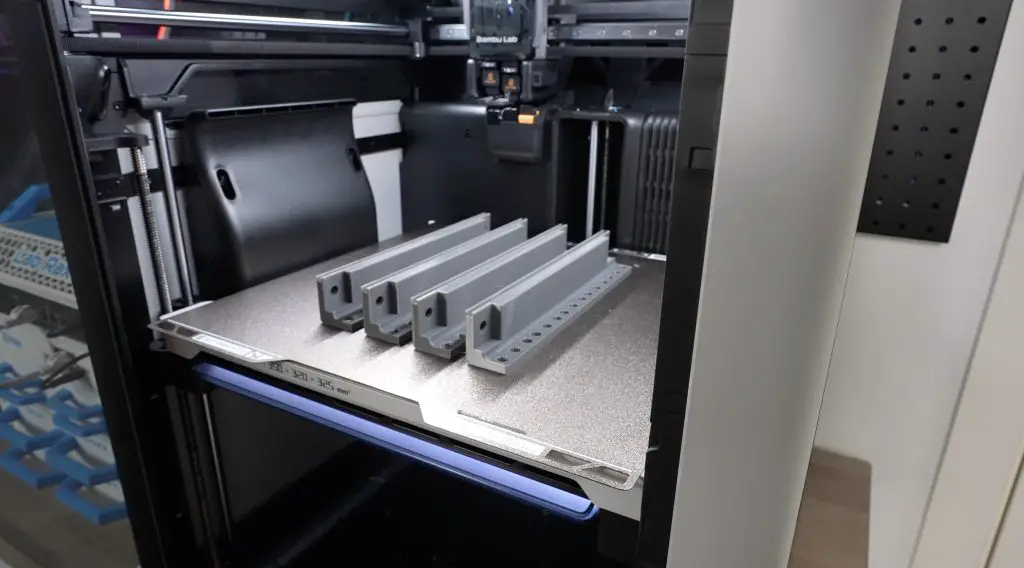

To evaluate thermal and performance characteristics, the system was populated with two full-size 3.5-inch WD Red NAS drives rated at 4TB each, along with 2TB Crucial P3 Plus NVMe drives installed in both available M.2 slots. With all drives installed, the system’s weight increased to 2.6 kilograms. This feels quite solid due to the metal construction and screw-mounted drive trays.

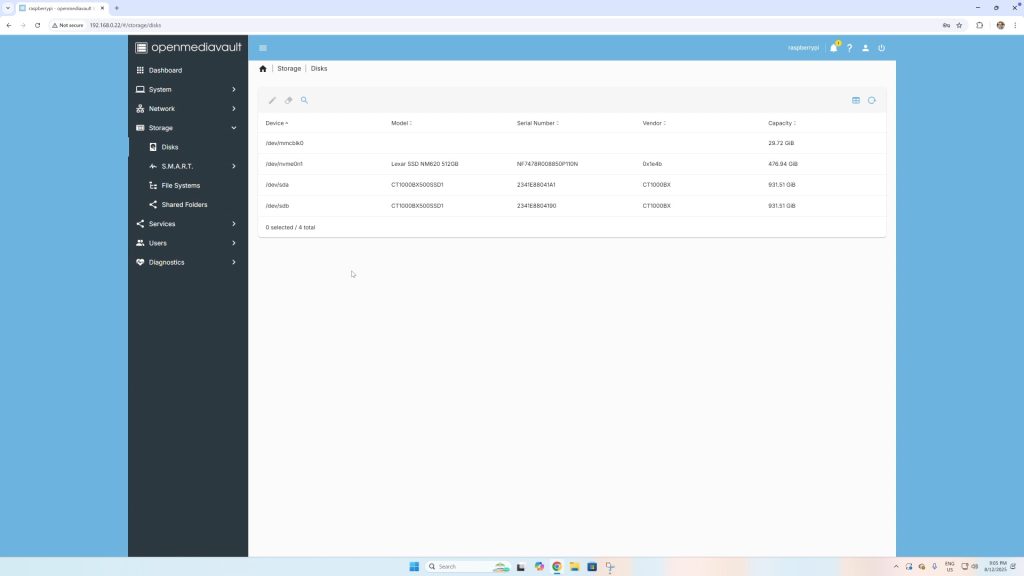

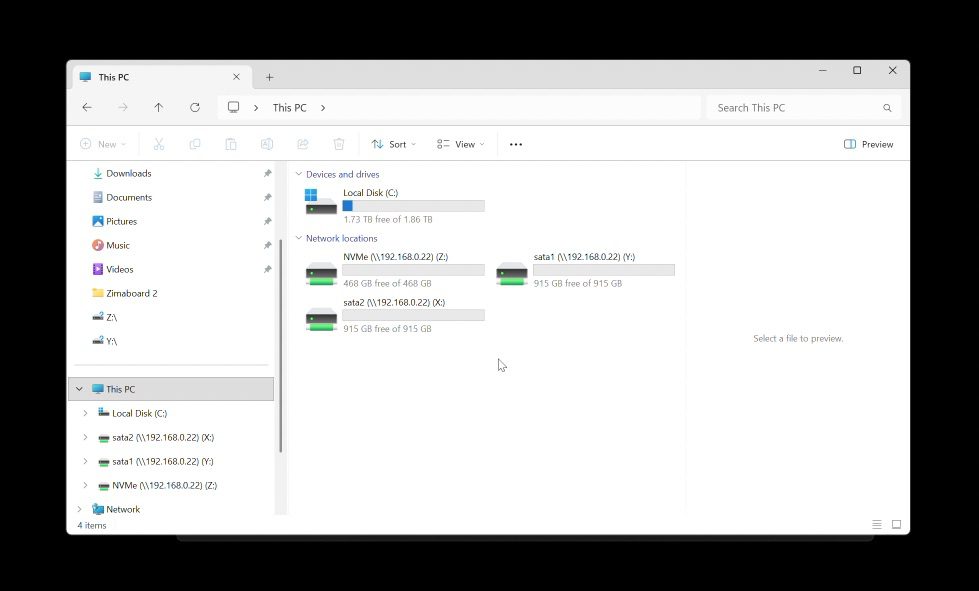

The ME Pro ships with Windows 11 preinstalled, but it’s not locked to this operating system, allowing users to install alternatives such as TrueNAS, Unraid, or Proxmox, depending on their use case.

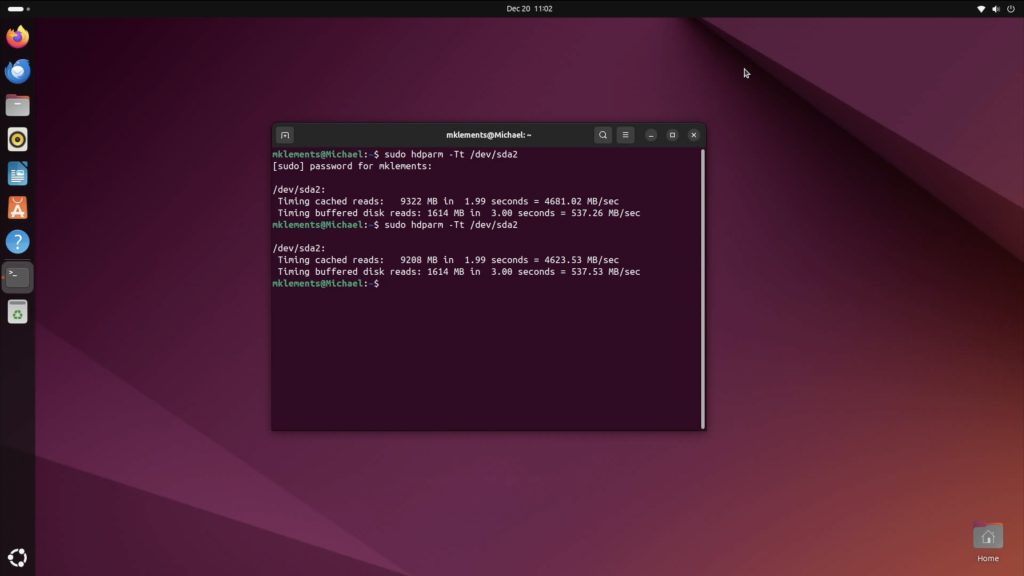

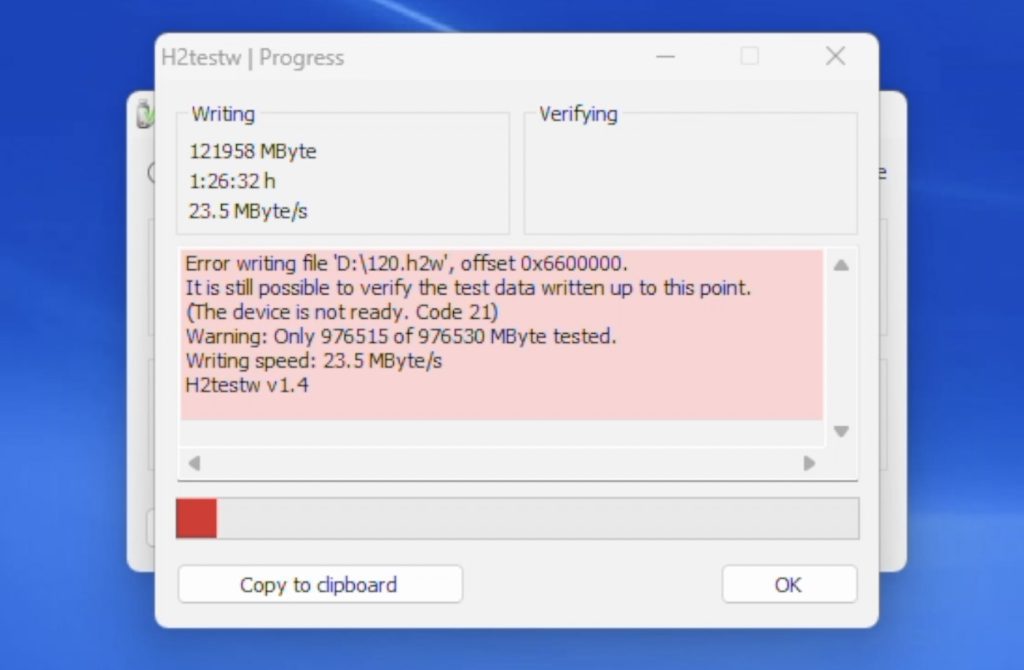

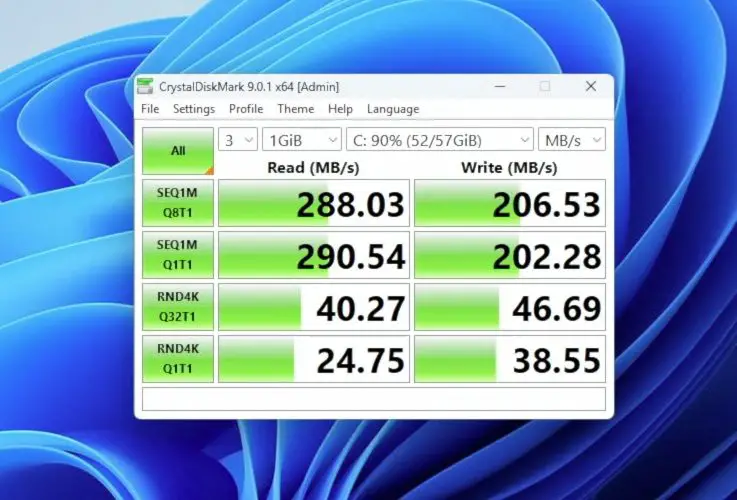

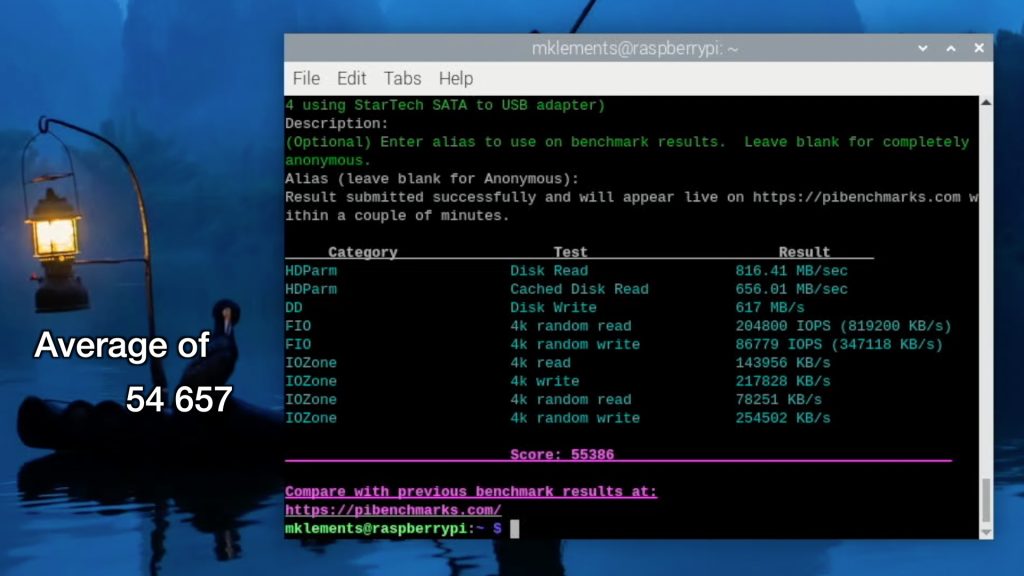

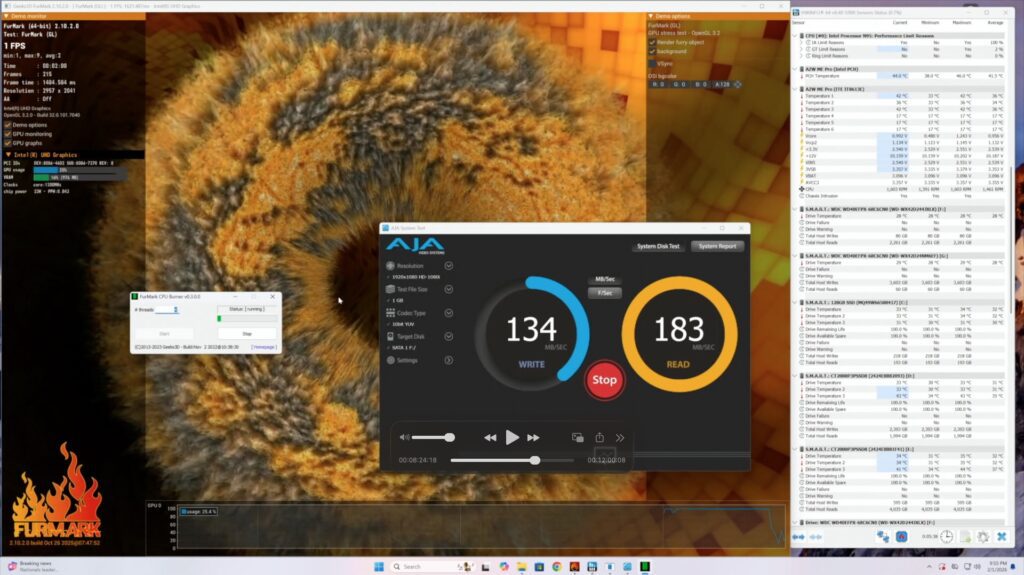

Storage Performance

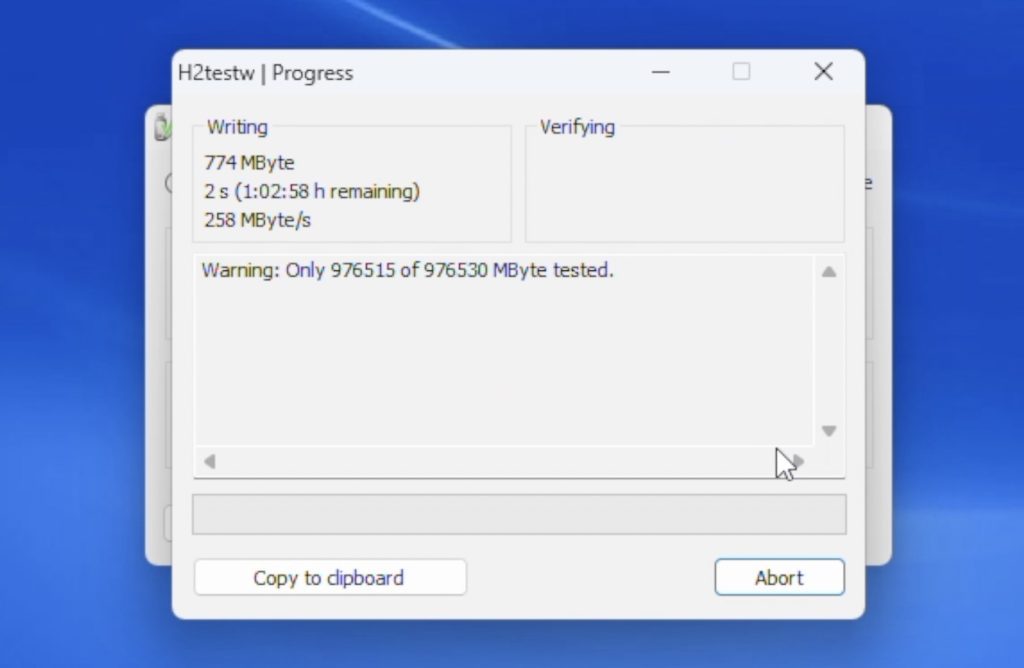

Drive performance testing was conducted by reading and writing files directly to each drive without caching. The SATA drives achieved write speeds of approximately 150MB/s and read speeds just under 200MB/s, with both drives delivering nearly identical results. The NVMe storage drives produced read and write speeds just below 800MB/s, again showing consistent results between drives. The operating system NVMe drive performed faster, achieving over 1000MB/s write speeds and just under 1500MB/s read speeds due to its additional PCIe bandwidth.

These results are right on what we’d expect from the available lanes, so the drives aren’t thermal throttling, and the controller and PCIe routing doesn’t seem to have any issues.

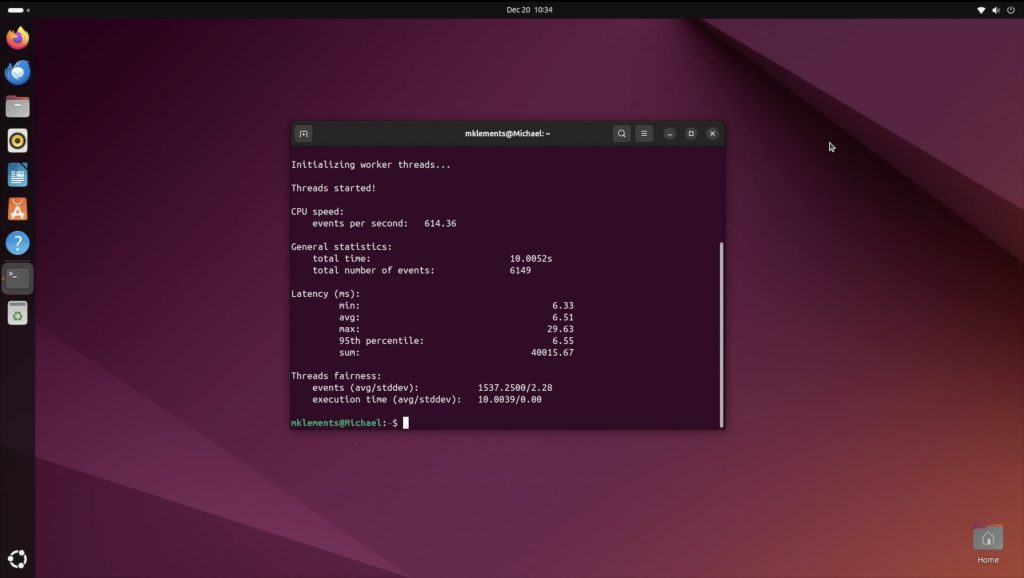

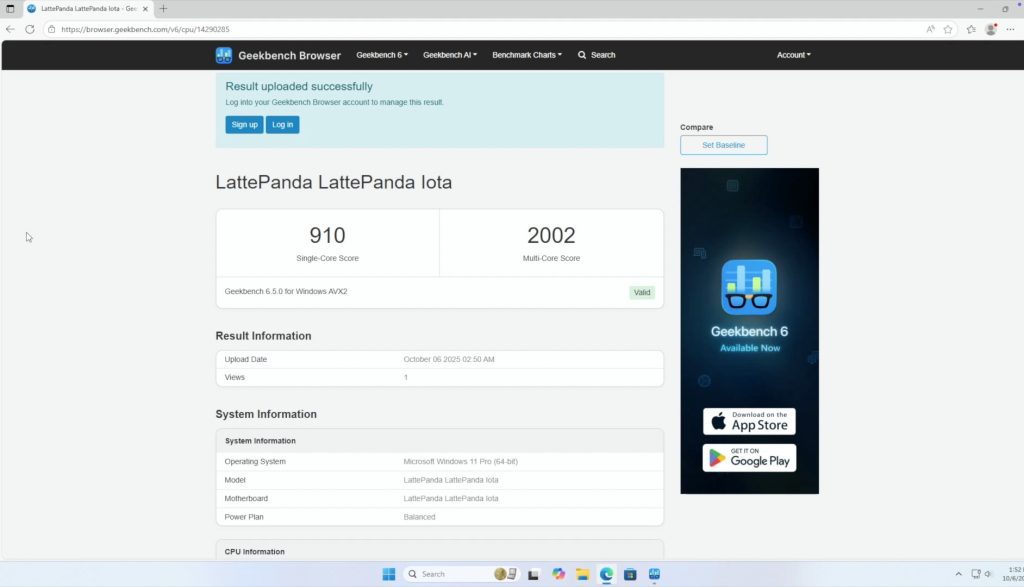

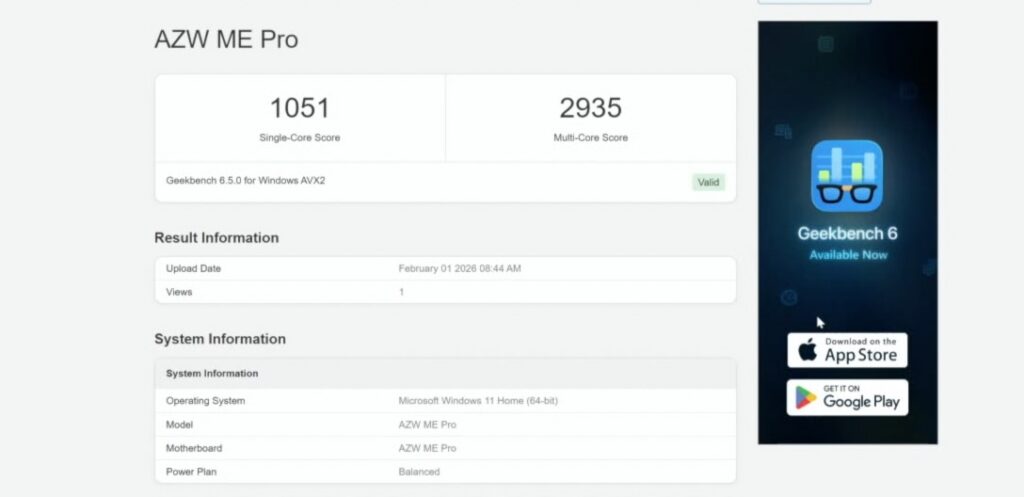

CPU Performance

Next, I tested the CPU. Geekbench 6 gives a cpu score of 1,051 single core and 2,935 multi-core. This is a low-power CPU, so we’re not expecting it to win any awards. The results are very roughly comparable to something like a Celeron J4125 or N5105 used in entry-level Synology or QNAP devices, but this one is probably a bit more power efficient.

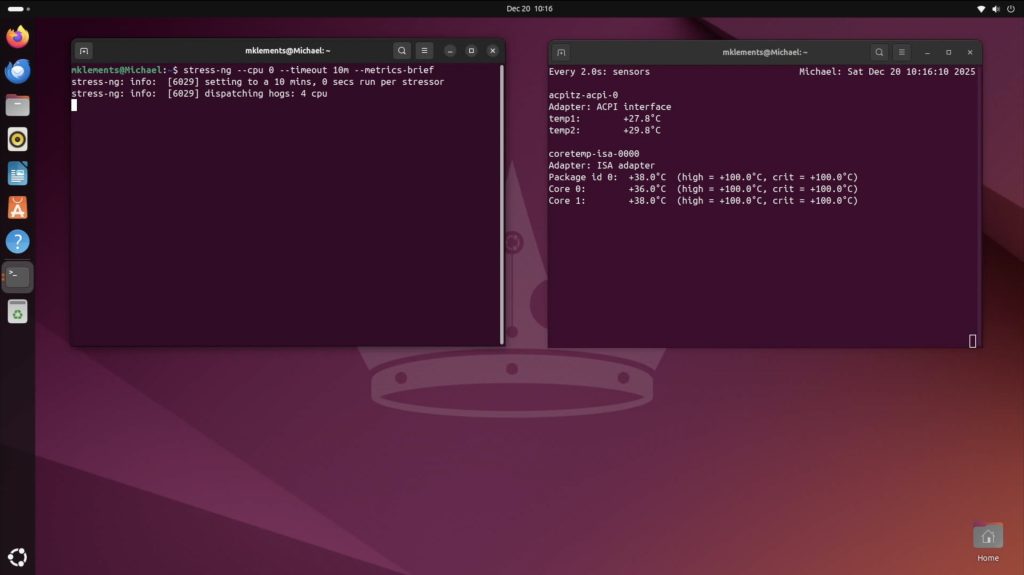

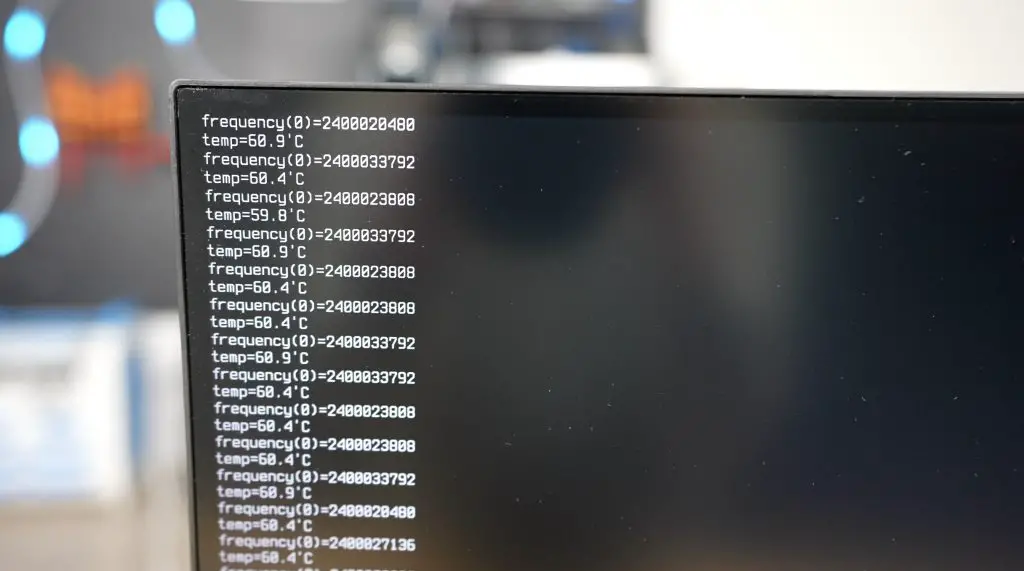

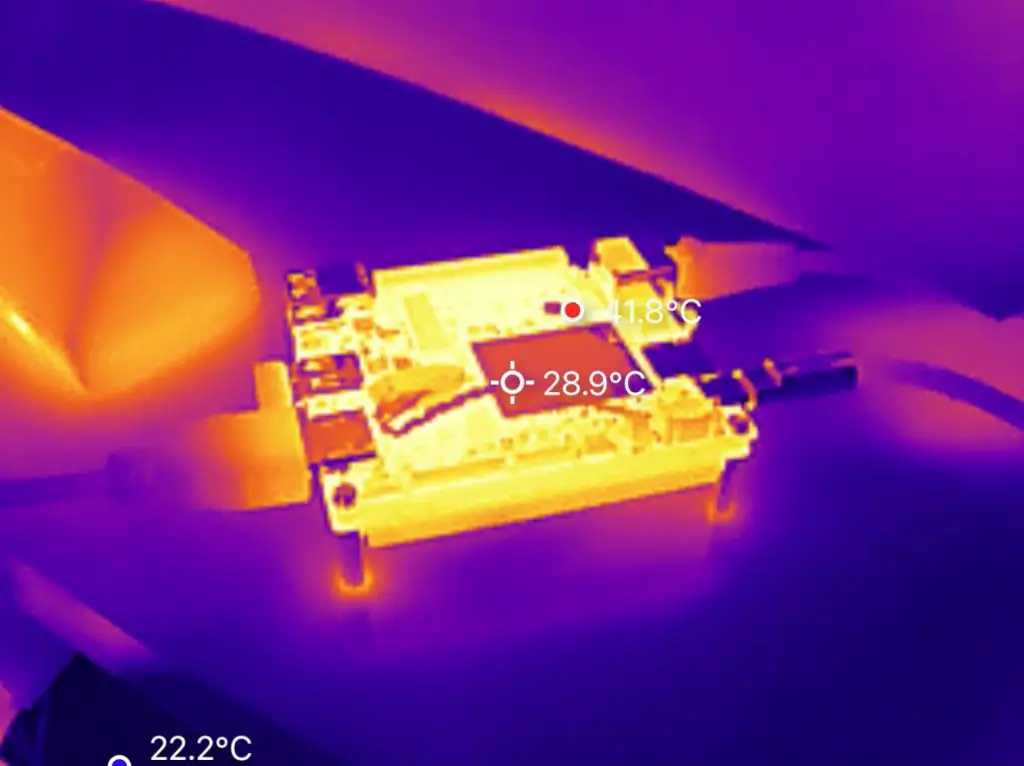

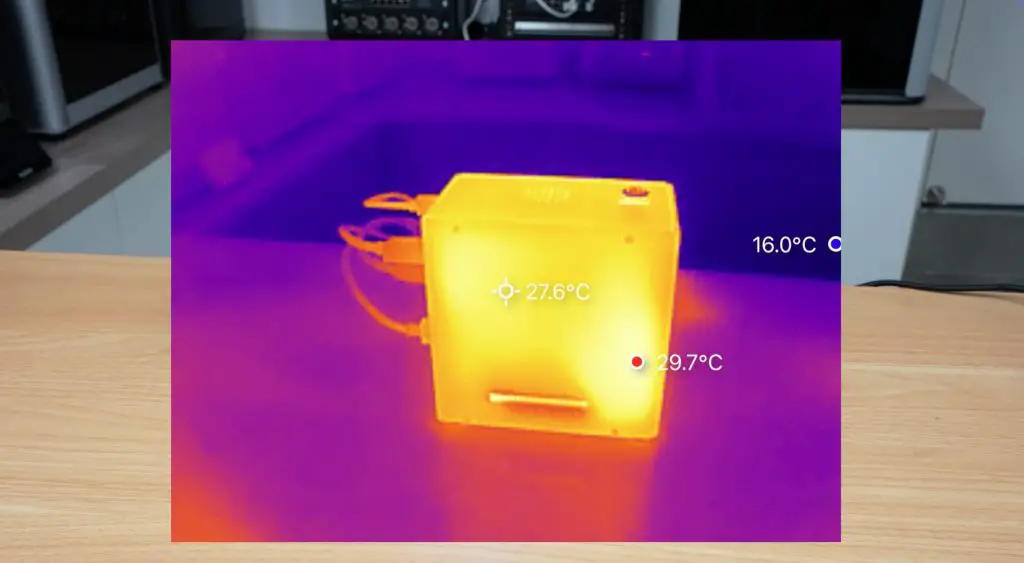

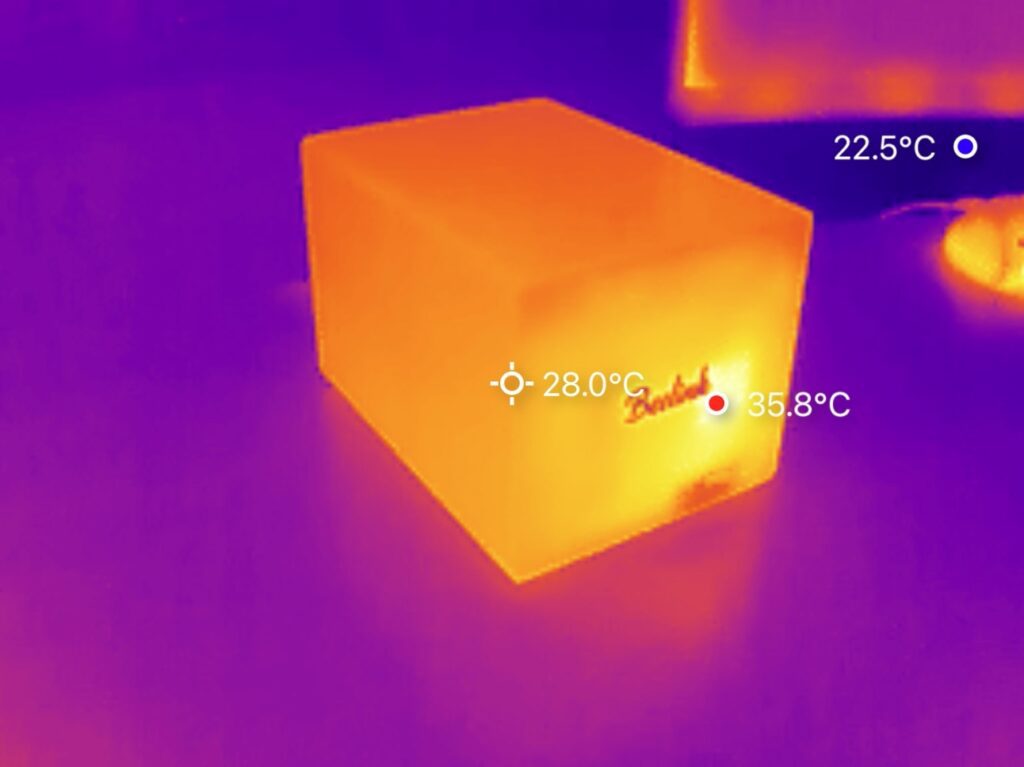

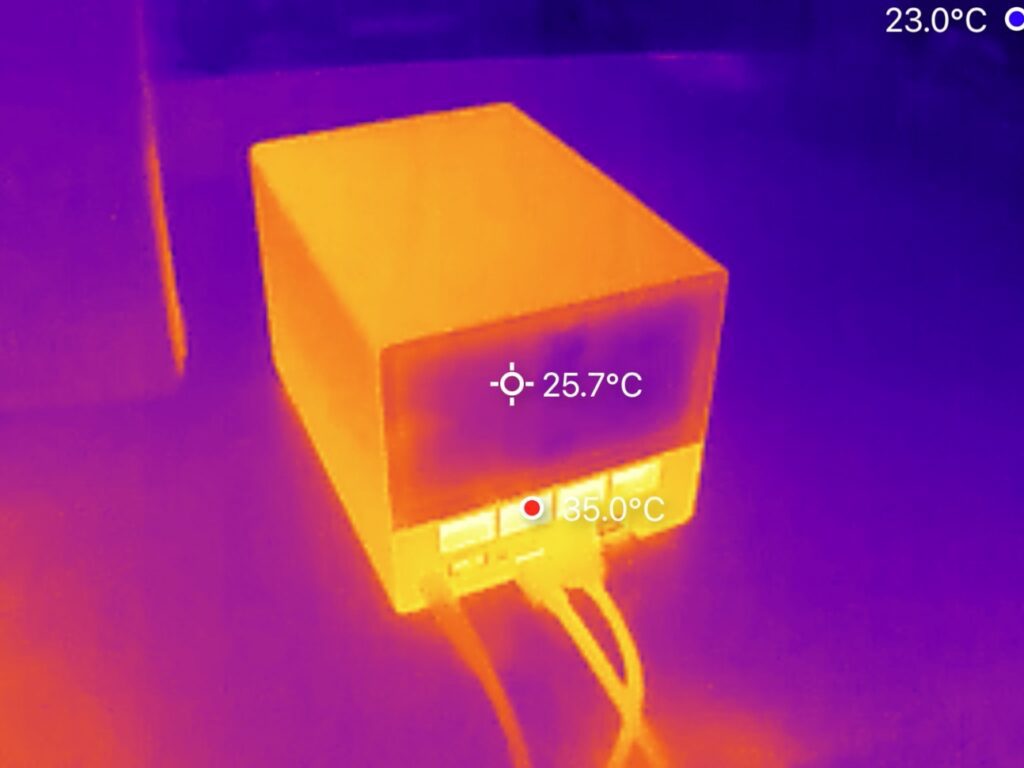

Thermal Performance

To test thermals, I ran Furmark for 30 minutes and had the drives under a read and write load. The CPU temperature began at 34 degrees Celsius while the drives idled between 28 and 30 degrees. After the stress test, the CPU temperature rose to only 50 degrees, and drive temperatures increased modestly to between 32 and 35 degrees. So the single blower fan cooling solution on this NAS is really effective.

Noise Levels

Speaking of the fan, in terms of noise level, it runs consistently under 32dB with the CPU fully loaded or at idle. Which is basically the lowest ambient sound level in my workshop and is near silent. With the mechanical drives being written to, you get an odd spike up to 33 dB, but that’s also quite near being silent and not something that you’d find distracting. Beelink have done very well at isolating noise on this unit, it’s by far the quietest NAS that I’ve used that has mechanical drives in it.

Network Performance

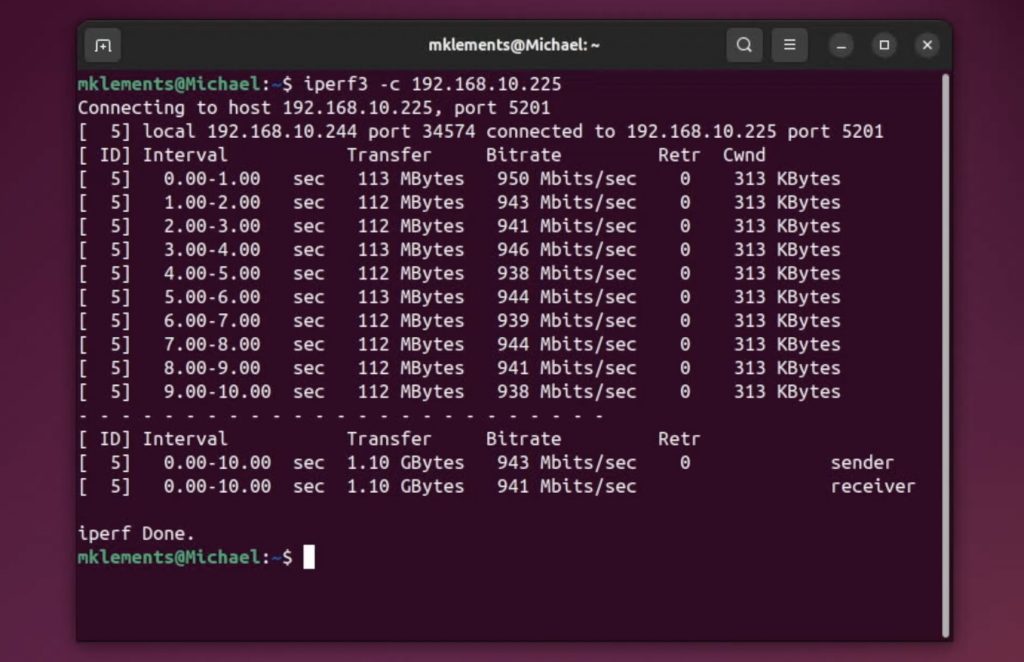

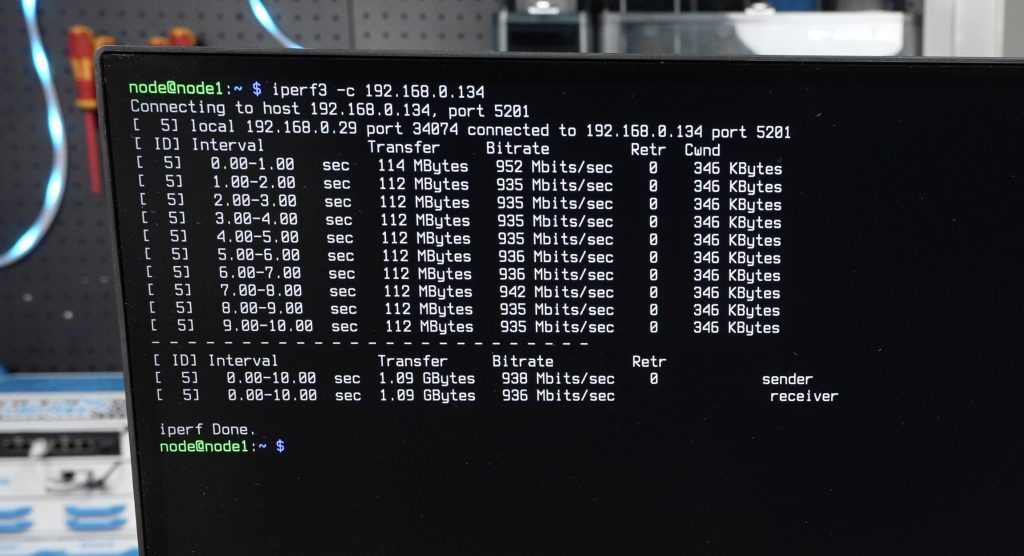

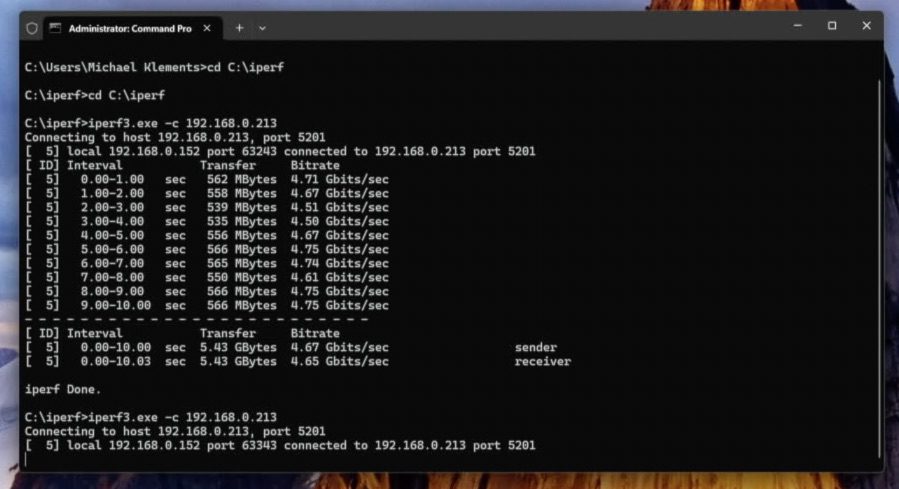

Network throughput was measured using iperf3 to isolate network performance from storage limitations. Testing on the 5-gigabit Ethernet port produced transfer speeds between 550MB/s and 560MB/s, which is consistent with expected real-world performance for this interface. Testing on the 2.5-gigabit port resulted in speeds of approximately 280MB/s, again matching expected throughput.

So both NICs are capable of running at their rated speeds. Some low-power mini PCs would struggle to saturate a 5-gigabit connection, but the N95 has no trouble doing so.

In real-world terms, the two mechanical drives would top out before the network does on the 2.5 gigabit port, and so the 5 gigabit port is only really going to be useful for your NVMe storage or for serving multiple clients at once.

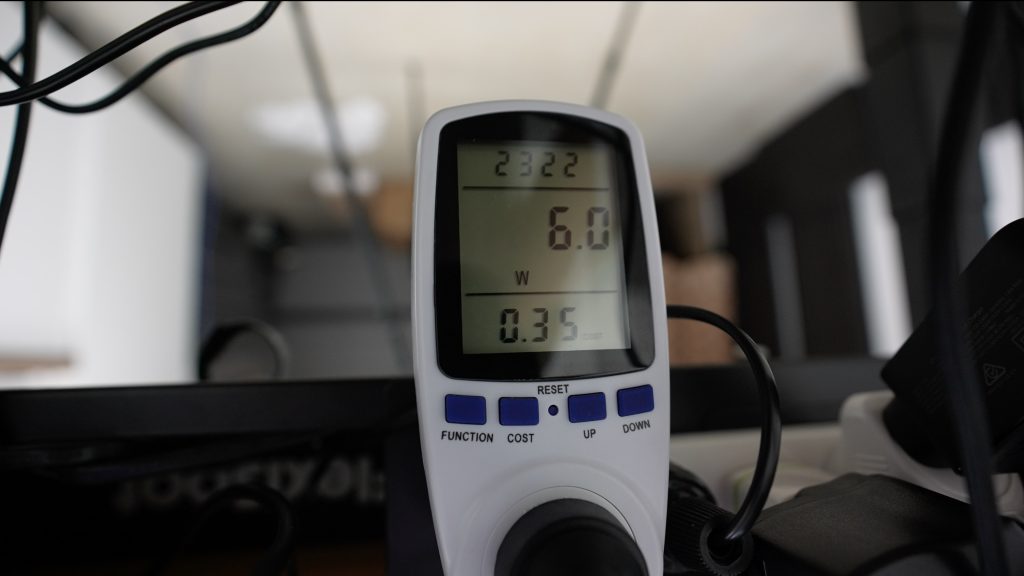

Power Consumption

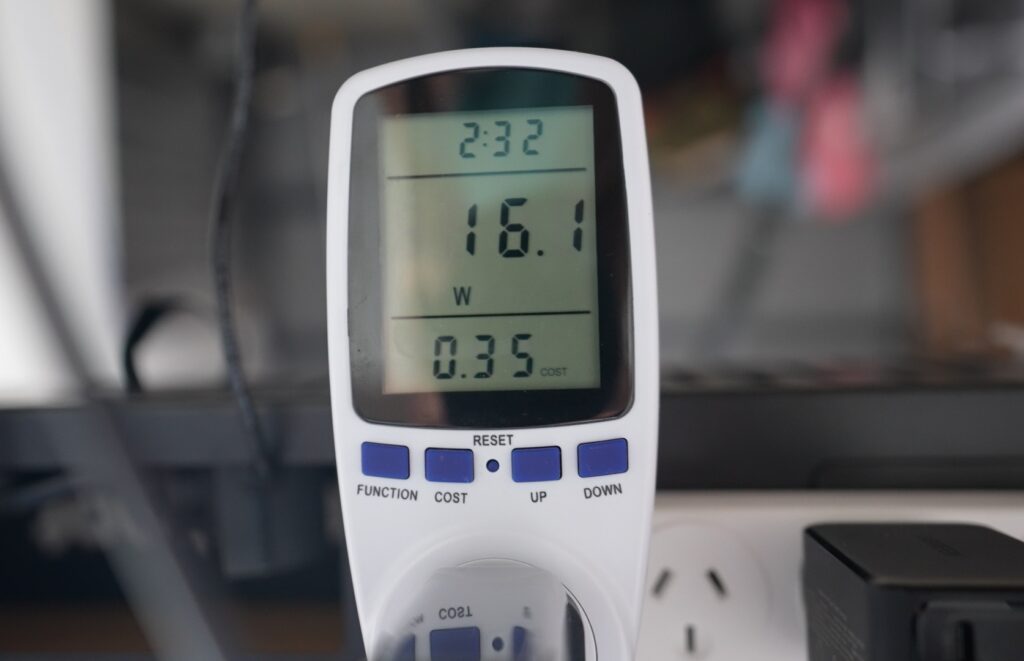

Finally, I tested power consumption. At idle with no drives installed, the system draws about 16W. With all drives installed and spun up, but not under a write load, idle power increases to around 22W and under full CPU and GPU load, as well as actively writing to one drive, power increases to 44W. Even at the top end, this is very good for the networking and drive performance that this NAS can deliver. This also makes it a great option for those in areas where power is expensive, since it’s going to be running 24/7.

Pricing and Value

Pricing is pretty good. I think the lower-end models are really good value for money, starting at $369 for the base N95 version with 12GB of RAM and 128GB of OS storage, and increasing to $479 for the same version with 1TB of storage. The N150 versions do go up a bit, so I’d probably only look at these models if you’re really going to be using the increase in CPU and RAM. These top out at $559 for the version with 16GB of RAM and a 1TB OS drive.

Final Thoughts

So, if you’re looking for a compact NAS or home server that offers multi-gig networking, NVMe storage, and good power efficiency, the ME Pro delivers exactly that.

It’s not trying to replace a high-end mini PC or NAS, but as a storage-focused home system, it’s well balanced and does what it says on the product page.

You get a solid set of ports and features, performance that matches the hardware, and with Beelink already working on additional motherboard options, the platform also looks like it could become quite modular over time.

As always, if you’ve got any questions or want to see specific workloads tested, let me know in the comments section below, and I’ll try test them out and add them to my results.